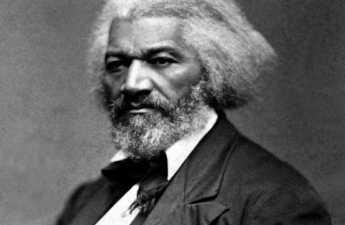

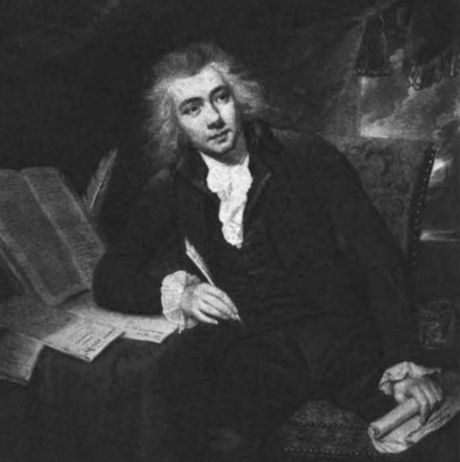

William Wilberforce (1759-1833) was the great English Christian statesman famous for playing a key role in abolishing the British slave trade.

He served in politics in the early days of the vaccination craze. Smallpox inoculation was originally performed with “smallpox matter” derived from people. It would be replaced by “cowpox matter” derived from cows (at least officially, although it could have matter from people as well). The former was called smallpox variolation, and the latter was called smallpox vaccination (even though both are forms of inoculation and both are what we would consider today as vaccination).

Both were peddled on the idea that they generated immunity from smallpox. But what they both were in reality was blood poisoning in the name of medicine.

Wilberforce was a mixed bag on this issue. On the one hand, he saw smallpox variolation as a dangerous spreader of smallpox, and thus should at least be restricted. On the other hand, he exchanged one version of blood poisoning for another — hastily embracing smallpox vaccination after Edward Jenner popularized it.

(If only Wilberforce saw through vaccination as his mentor John Newton did.)

In a public meeting in 1803, Wilberforce condemns smallpox variolation as dangerous but also openly advocates — if not urges the enforcement of — the newer from of inoculation, smallpox vaccination. Here is where a one William Cobbett comes in. Cobbett took Wilberforce as wanting to mandate vaccination, and thus appeals with him to rethink his position. (Indeed, it is quite inconsistent to oppose the slave trade while also supporting medical slavery.)

Cobbett thus instructs Wilberforce on enforced vaccination being antagonistic to the very liberties Wilberforce champions. Whether or not Wilberforce was actually pushing to enforce vaccination, Cobbett’s words are instructive to anyone advocating vaccine tyranny:

SIR,-Before I proceed to the remaining points of my proposed discussion, I think it necessary to notice a new project, in which you appear to have taken a leading part, and which has, in my opinion, a tendency extremely dangerous to the real freedom and happiness of the country.

You will easily perceive, that I allude to your strange proposal for effecting a compulsory adoption of the new system of inoculation. At a meeting held by a Society, formed for the purpose of “exterminating the small-pox,” held at the London Tavern on the 19th instant, you and a DR. CLARKE, are reported, in the public papers, to have expressed your selves as follows:-

“MR. WILBERFORCE rose, and having questioned Dr. B. respecting the prejudices that still existed against this new inoculation, observed, that in his opinion the first step which the meeting should take would be to form a committee, and then to apply to parliament for its countenance and support. He observed, that it was a great national question; and he was confident that a petition to parliament would find very powerful succour; that it would call forth the exertions of the lord lieutenants of counties, and the magistrates and parish officers; and through their means the whole country would enjoy the benefit resulting from this discovery.”

– “DR. CLARKE followed much in the same strain; and observed that he thought that in future no person ought to practice the old mode of inoculation, except under very particular circumstances, and with the approbation of the civil magistrate, not that he wished to abridge the liberty of the subject, or to countenance the least interference of the state in matters relating to life and health, but that no one had a right to injure the community in the exercise of that privilege.”

-Now, Sir, without entering into any inquiry as to the merits of DR. JENNER’S system of inoculation, give me leave to ask you, how you can reconcile a proposition like this to the spirit of that constitution, of which you profess to be so great an admirer, and to that freedom, of which you wish to be regarded as one of the principal supporters?

That you agree with Dr. Clarke, that you have in view an Act of Parliament to compel people to have their children inoculated with the Cow Pox, or not to have them inoculated at all, is, I think, evident enough, else why “apply to Parliament for countenance and support?” Parliament has already given that countenance and support, which, supposing the discovery to be a good one, it was proper for it to give. It has munificently rewarded Dr. Jenner for his labours, and for communicating their result to the nation at large; and, having so done, it has left his system to that encouragement and support, which it will be sure to meet with from successful experience.

But, it seems, there are “prejudices” against this system, which it is necessary to destroy by force. Sir, that there are prejudices, and very strong ones too, I am ready to allow; and if I were to say, that: these “prejudices” extend to a very great majority of even the medical men, in the kingdom, I believe, I should not be erroneous in my statement. But, I cannot agree, that these “prejudices” ought to be eradicated by force; nor is it, perhaps, very fair to use this degrading term, as expressive of the dislike, which so large a portion of the community entertain to the system, which you are so anxious to compel them to adopt.

The charge of “prejudice,” Sir, has been preferred but too often and with but too fatal success, against every one opposed to change. How many millions of times has it been brought against the monarchists of France, and, in England, against the opposers of parliamentary reform? The truth is, that whoever has been found to object to innovation, however wild in itself, however destructive in its consequences, has constantly been accused of “prejudice;” and, as prejudice, thus used, implies a mixture of ignorance and perverseness, and, as few persons are willing to be thought ignorant and perverse, the dread of this imputation has most powerfully contributed towards the success of that system of plunder, of bloodshed, and of blasphemy, which has, for the last ten years, overwhelmed the nations of Europe.

But, why need I travel so far in search of facts to illustrate and establish my argument, when your society itself has furnished me with such excellent materials? There was, as you must well remember, Sir, a strong and very general objection, which, for a long time, prevailed against the old system of inoculation; and you cannot have forgotten, that this objection was termed “prejudice,” and the persons entertaining it were regarded as illiterate, ignorant, or perverse; yet, it now appears from the address of your society to the public, that it would have been well for the human race, if the “prejudice” of those “illiterate, ignorant, or perverse” persons had universally obtained; for you now tell us, that inoculation [via variolation – editor], by spreading the “contagion, has considerably increased its mortality.”

With an example like this before our eyes, Sir, ought we not to be very cautious how we adopt a new system of inoculation?-But, it is not to the endeavours of your society that I object. Those endeavours seem to be directed to the mere encouragement of a system, of the good effects of which they are fully persuaded. In their resolutions and addresses, they propose no force. So far all may be right.

What I am opposed to, what I am alarmed at, is the proposition of you and Dr. Clarke, to obtain, for the support of the system, an Act of Parliament, which would, in its operation, be nothing short of a compulsion on every man to suffer the veins of his child to be impregnated with the disease of a beast, or, to expose its life to the utmost violence of the most furious and most fatal of all human contagions-a measure to be adopted in no country where the people are not vassals or slaves.

– I like not this neverending recurrence to Acts of Parliament. Something must be left, and something ought to be left, to the sense and reason and morality and religion of the people. There are, as I observed on a former occasion, a set of “well-meaning men” in this country, who would pass laws for the regulating and restraining of every feeling of the human breast, and every motion of the human frame: they would bind us down, hair by hair, as the Liliputians did Gulliver, ’till anon, when we awoke from our sleep, we should wonder by whom we had been enslaved.

But, I trust, Sir, that the Parliament is not, and never will be, so far under the influence of these minute and meddling politicians, as to be induced to pass laws for taking out of a man’s hands the management of his household, the choice of his physician, and the care of the health of his children; for, under this sort of domiciliary thraldom, to talk of the liberty of the country would be the most cruel mockery where with an humble and subjected people was ever insulted.

Cobbett’s Weekly Political Register, Vol. III., No. 4, London, Saturday, January 29th, 1803, in Cobbett’s Weekly Political Register, Vol. III, 97-100. I have made multiple paragraphs out of the text (originally one paragraph) for better readability.

Was Wilberforce actually misunderstood and not in support of mandatory vaccination; or, did he at least change his mind at some point? I’m not sure. The National Anti-compulsory-vaccination Reporter writes this about Wilberforce, but it is not clear to me when it was said, and if it had to do with vaccination:

Mr. Wilberforce was also opposed to compulsion. His words in Parliament were “I think compulsion would be absolutely wrong. This is my most deliberate opinion.”

The National Anti-compulsory-vaccination Reporter, Vol. III, No. 1, October 5, 1878, 18.

In any case, in 1806 (three years after Cobbett’s complaint about Wilberforce wanting to enforce vaccination), Wilberforce, in the House of Commons, is mildly pro-enforcement. Generally, he urges quarantine for those suffering from smallpox to keep it from spreading — but it only applies to the unvaccinated! (As if it is okay to spread smallpox if you are vaccinated!)

However, in this talk, Wilberforce especially urges restrictions on smallpox variolation (namely, temporary quarantine to keep the recently inoculated patient from spreading smallpox), which is not so bad, considering the practice is blood poisoning; if only he was consistent and opposed smallpox vaccination as well:

Although I agree with the noble lord, that compulsory measures, in such cases ought carefully to be avoided, if possible; at the same time I think there is another method which may be adopted with absolute justice and propriety. Although we cannot force people to inoculate with the vaccine matter, in preference to that of the small pox [via vaccination instead of variolation — editor], yet we may impose certain rules, or restrictions, on those who do put the latter practice into execution upon their children.

This would contribute greatly to secure the public against the effects of contagion, in the same manner as is done in the case of the plague. The laws of quarantine have continued long enough to be enforced, and have been found to be attended with infinite advantage. These may be deemed a constraint upon the public, but having proved so beneficial, why not impose the same control over mankind in other cases where communications with the diseased may be attended with dangerous consequences?

Now we know, sir, that the small pox has been found by long and fatal experience, to be nearly a kind of plague, so that great advantage would arise to society were we to prohibit persons who do not vaccinate their children, from allowing them, when labouring under the small pox, to go out amongst others who have hitherto escaped its dreadful consequences.

The present permission of variolated patients going abroad amongst society is not productive of any advantages, either to the children themselves, or their parents. If we found that the parents were not willing to confine their children in their own houses, would there not be an evident propriety in government having places appointed for that express purpose? I only throw out these hints, as I think it is a thing which gentlemen ought to hold in their minds.

House of Commons, Wednesday, July 2, 1806. The Parliamentary Debates from the Year 1803 to the Present Time: Volume VII: Comprising the Period from the Sixth Day of May to the Twenty-Third Day of July 1806. (London: T.C. Hansard, 1812), 886, 887. I have made multiple paragraphs out of the text (originally one paragraph) for better readability.

At least we can say that Wilberforce did not speak of smallpox variolation (the forerunner to vaccination — vaccination in all but name) in glowing terms — unlike what we might hear from some vaccine propagandists today.

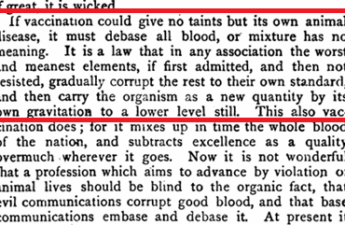

So Wilberforce is better than today’s extremists who act as if no wrong can come from any vaccine; but still, being “moderate” is not enough when it comes to promoting health. Blood poisoning is blood poisoning, no matter the kind of vaccine — whether it is via smallpox or cowpox, a live or inactivated vaccine, a single or triple vaccine, a “tested” or untested vaccine, an mRNA or traditional vaccine, etc.

If you find this site helpful, please consider supporting our work.