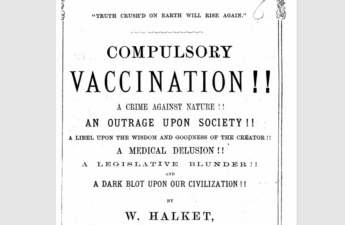

by Steve Halbrook

Note regarding Cotton Mather: before reading this article, let me say at the outset that despite Mather’s role in popularizing a murderous procedure, I believe, based on his diary, that he sincerely believed smallpox inoculation to be of benefit to mankind, and had no ill-intent. So this article is not judging his sincerity. Moreover, I am not questioning his salvation in Christ. This article is simply warning about the consequences (in this case severe) of promoting an ill-conceived practice, which any one of us can do.

Simply peruse pro-vaccine history propaganda, and you will almost always find the name Cotton Mather among the “heroic pioneers” of this procedure. Sadly, even though Christians should be leading the way in matters of truth, Christian “scholarship” employs him as the poster child for popularizing a “great scientific procedure that saved countless lives.”

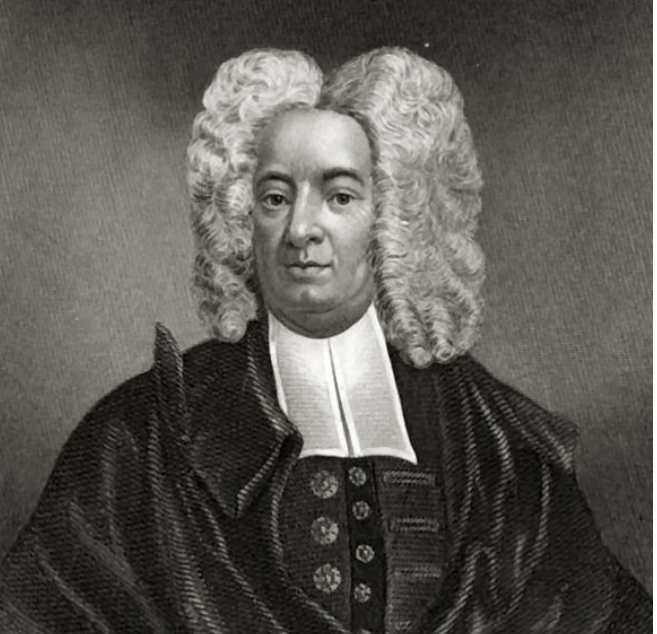

Cotton Mather (1663-1728) was a Puritan clergyman in New England. He introduced the colonies to smallpox variolation, or inoculation, in 1721 to combat the spread of smallpox.

Smallpox variolation is technically the forerunner to vaccination, but in essence it is the beginning of vaccination; vaccination in all but name (and both practices can be referred to as “inoculation”). Smallpox variolation inoculates one with smallpox in the name of fighting smallpox, while smallpox vaccination — which replaced it — inoculates one with cowpox in the name of fighting smallpox.

While vaccine lore asserts that smallpox variolation was a “miraculous blessing” to mankind, nothing can be farther from the truth. In fact, it was finally acknowledged to be a dangerous practice that required criminalization.

Sadly, one plague was replaced by another, with smallpox variolation replaced by smallpox vaccination. From the time of smallpox variolation to today, vaccination has left a trail of divisiveness, deception, idolatry, and genocide.

And the spark, at least in America, was smallpox variolation — ignited by Cotton Mather.

My hope is that this article helps the church learn from history so that we do not repeat the mistakes — and even sins –of the past.

Note: since the terms variolation and inoculation can be used interchangeably, to be consistent with the sources we quote, we will henceforth usually use the term inoculation to refer to smallpox variolation.

Sections in this article include:

- Inoculation self-evidently a disgusting, unsanitary practice

- The tragedy begins

- The division starts

- Smallpox inoculation shown to be deadly

- Smallpox inoculation shown to be worthless, spreading smallpox and death

- Smallpox inoculation (in the form of variolation) criminalized

- The tragedy of Jonathan Edwards

- Smallpox threat tended to be exaggerated

- Vaccine deaths and denying the obvious: here from the outset

- A Biblical critique of inoculation

- Inoculation fosters mistrust of the clergy

- When vaccine harm comes: calling out to God

Inoculation self-evidently a disgusting, unsanitary practice

It is amazing how so many would eventually embrace such an obviously disgusting, unsanitary practice as smallpox inoculation. The following should sufficiently address this point:

The word [inoculation] is derived from the Latin inoculare, meaning “to graft.” Inoculation referred to the subcutaneous instillation of smallpox virus into nonimmune individuals. The inoculator usually used a lancet wet with fresh matter taken from a ripe pustule of some person who suffered from smallpox. The material was then subcutaneously introduced on the arms or legs of the nonimmune person. … However, inoculation was not without its attendant risks. There were concerns that recipients might develop disseminated smallpox and spread it to others. Transmission of other diseases, such as syphilis, via the bloodborne route was also of concern.

Stefan Riedel, Edward Jenner and the history of smallpox and vaccination, Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings (January 2005, 18(1): 21–25. Retrieved May 2, 2024, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1200696

Simply considering God’s natural design should repel anyone from even entertaining the use of inoculation. The perverse procedure is an outrage against God’s created order. God gave us skin as a protective barrier to keep foreign matter out of the blood — not to insert it. Moreover, poisoning one’s blood with diseased filth from another person is incredibly reckless and hazardous.

That inoculation was a sower of disease, instead of a suppresser of it (as time would show), should have easily been anticipated.

And on top of this, inoculation fails to count the cost. Inoculation is not an emergency medical procedure — where a certain health risk must be taken to prevent an existing greater health danger (not that inoculation would even be appropriate here) — but a possible preventative for something that may or may not occur in the future. A definite danger in the name of maybe stopping a possible danger!

Such considerations should tell anyone that inoculation is a violation of the Sixth Commandment; a doing of evil that good may come.

And so had Cotton Mather simply considered God’s natural design, then he would have spared Boston of the carnage to come. But he stubbornly determined to push a practice that would unwittingly lead to the blood poisoning and even deaths of countless people.

The tragedy begins

The tragedy of Cotton Mather begins thus:

Dr. Cotton Mather, of Boston, had observed in the philosophical transactions, an account of the manner in which inoculation for the small pox was practised in the Turkish dominions.

Samuel Williams, The Natural and Civil History of Vermont, Volume 1 (Burlington, VT: Samuel Mills, 1809), 460.

With smallpox visiting Boston, Mather proposed this as a means to stop the spread. When he tried to convince the town’s physicians of it, they rightfully rejected this unnatural, dangerous procedure. They saw it for what it was: an outrage against God’s created order.

At this point we will draw from the work of Nathaniel Hawthorne (yes — the Nathaniel Hawthorne of The Scarlet Letter). You can tell by the language that he has a pro-inoculation bias, but he at least captures the situation in detail.

Hawthorne begins with the reaction of the town physicians to Mather’s proposal:

But the grave and sagacious personages would scarcely listen to him. The oldest doctor in town contented himself with remarking that no such thing as inoculation was mentioned by Galen or Hippocrates; and it was impossible that modern physicians should be wiser than those old sages. A second held up his hands in dumb astonishment and horror at the madness of what Cotton Mather proposed to do. A third told him, in pretty plain terms, that he knew not what he was talking about. A fourth requested, in the name of the whole medical fraternity, that Cotton Mather would confine his attention to people’s souls, and leave the physicians to take care of their bodies.

In short, there was but a single doctor among them all who would grant the poor minister so much as a patient hearing. This was Doctor Zabdiel Boylston, He looked into the matter like a man of sense, and finding, beyond a doubt, that inoculation had rescued many from death, he resolved to try the experiment in his own family.

And so he did. But when the other physicians heard of it they arose in great fury and began a war of words, written, printed, and spoken, against Cotton Mather and Doctor Boylston. To hear them talk, you would have supposed that these two harmless and benevolent men had plotted the ruin of the country.

Nathaniel Hawthorne, A wonder-book. Tanglewood tales. Grandfather’s chair (Boston, MA: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1883), 522.

The division starts

Before the carnage caused by inoculation, the division came. The other doctors rightfully publicly opposed this obviously unnatural and dangerous practice. Had Cotton and Doctor Zabdiel Boylston listened to reason, the Christians in Boston would have been spared unnecessary strife:

The chief proponents of inoculation, Cotton Mather and Dr. Zabdiel Boylston, were supported by a very small coterie of ministers and doctors. The opponents on medical grounds, led by Dr. William Douglass, the only trained medical doctor in town, included most of the other physicians, the town selectmen, and editor James Franklin of the New England Courant, a paper founded in the midst of the controversy to give opponents a forum.

Patricia Cline Cohen, A Calculating People: The Spread of Numeracy in Early America (New York, NY: Routledge, 1999), 96.

Battle lines were drawn; the matter became a topic in sermons, and a

paper war ensued as each side published pamphlets and newspaper articles to argue its position and refute its opponents. At times the debate became personal and biting, each side accusing the other of bias and falsification.

National Humanities Center, The Paper War over Smallpox Vaccination in Boston, 1721, Selections., 1. Retrieved February 28, 2015

Hawthorne (again, writing with a pro-inoculation bias) writes:

The people, also, took the alarm. … Some said that Doctor Boylston had contrived a method for conveying the gout, rheumatism, sick-headache, asthma, and all other diseases from one person to another, and diffusing them through the whole community.

The people’s wrath grew so hot at his attempt to guard them from the small-pox that he could not walk the streets in peace. Whenever the venerable form of the old minister, meagre and haggard with fasts and vigils, was seen approaching, hisses were heard, and shouts of derision, and scornful and bitter laughter. The women snatched away their children from his path, lest he should do them a mischief. …

Hawthorne, A wonder-book. Tanglewood tales. Grandfather’s chair, 522, 523.

Barrett Wendell notes the division that inoculation caused even within Mather’s family:

“It [Mather’s recommendation for inoculation] raised an horrid Clamour.” In July, this clamour was all about him. Quarrels with his step-children, the Howells, whose estate he had tried to administer, vexed him, at the same time; to meet their claims, he had even to sell some of his clothing.

Barrett Wendell, Cotton Mather, the Puritan Priest (NY: Dodd, Mead, and Company, 1891), 276.

According to Britannica,

When Cotton inoculated his own son, who almost died from it, the whole community was wrathful, and a bomb was thrown through his chamber window.

Britannica, Cotton Mather (Last Updated: Mar 26, 2024). Retrieved April 18, 2024, from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Cotton-Mather

Hawthorne elaborates on this bomb,

One night a destructive little instrument, called a hand-grenade, was thrown into Cotton Mather’s window, and rolled under Grandfather’s chair. It was supposed to be filled with gunpowder, the explosion of which would have blown the poor minister to atoms. But the best informed historians are of opinion that the grenade contained only brimstone and assafoetida, and was meant to plague Cotton Mather with a very evil perfume.

Hawthorne, A wonder-book. Tanglewood tales. Grandfather’s chair, 524, 525.

When people feel their community is threatened, and/or their sense of justice is violated (in both cases here, by inoculation), they sometimes resort to sinful actions (as in above). They should not take the law into their own hands. However, the civil magistrates should have immediately halted the practice by criminalizing it. Unfortunately,

The House of Representatives passed a bill prohibiting inoculation under severe penalties, but it never became a law.

Francis Randolph Packard, The History of Medicine in the United States (Philadelphia, PA: J.B. Lippincott, 1901), 79.

And so we can see, people on both sides went to far: Unwitting acts of violence by the pro-inoculaters (due to the dangers of inoculation and their unwillingness to listen to reason), and at least one anti-inoculater throwing into Mather’s house a stink bomb at best, or a deadly bomb at worst. And of course, uncharitable words on all sides. Sad to see a Christian community degenerate in this way.

Smallpox inoculation shown to be deadly

Even before its eventual criminalization, smallpox inoculation was recognized as dangerous — even in its beginnings in Boston and England (where it was promoted by others at the same time that Mather did so in Boston).

As early as 1722, Isaac Massey, an apothecary to Christ’s Hospital in London, sums up inoculation as thus:

Inoculation is an Art of giving the Small Pox to Persons in Health, who might otherwise have lived many Years, and perhaps to a very old Age without it, whereby some unhappily come to an untimely Death …

Isaac Massey, A Short and Plain Account of Inoculation: With Some Remarks on the Main Arguments Made Use of to Recommend that Practice, by Mr. Maitland and Others (London: W. Meadows, at the Angel in Cornhill, 1722), 1.

In Boston, an outspoken critic of inoculation was a physician named William Douglass. Dr. Douglass describes the effects of inoculation in this way:

By Affidavit and Declarations lately published, we find that the Inconveniencies or Diseases proceeding from the Inoculation are of three Sorts. The First are the high Fevers and other dangerous Symptons immediately attending the Inoculation. . . The other two Risks are what our inoculated Objects have still to apprehend, viz. Impostumations and Ulcers in the Vicera or Bowels, Groin, and other glandulous Parts, Loss of the Use of their Limbs, Swellings &c., occasioning Death or miserable Remnant of Life, much analogous to that of Venereal Infection which . . . in process of time [results in] sordid Ulcers, Caries or rottenness of the Bones, destroys or renders the Patient miserable for Life.

Dr. William Douglass, The New-England Courant, August 14-21, 1721. Cited in National Humanities Center, The Paper War over Smallpox Vaccination in Boston, 1721, 3.

According to Douglass, inoculation could cause abortions:

Their Daring Practice on Women with Child who miscarry‘d while under Inoculation, they do not mention, as if procuring Abortion were a very innocent Practice, I forbear the Names of some who are instances of this Wickedness.

William Douglass, Inoculation of the Small Pox as Practised in Boston, Consider’d in a Letter to A-S– M.D. & F.R.S. in London (Boston, MA: J. Franklin, 1722), 12.

Elsewhere, Douglass writes,

We all knew of nine or ten inoculation deaths, besides abortions that could not be concealed. We suspect more who died in the height of smallpox, it being only known to their nearest relations whether they died of inoculation or in the natural way.

William Douglass: Against Inoculation for Smallpox. Cited in The Annals of America: Volume 1: 1493-1754: Discovering a New World (Chicago, IL: William Benton, Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc., 1968), 348.

Douglass would later change his position on smallpox inoculation. He said in 1751:

The Novel Practice of Procuring the Smallpox by Inoculation, is a very considerable and most beneficial Improvement in that Article of medical Practice. It is true, the first promoters of it were extravagant, and therefore suspected in their Recommendations of it; and some Writers instance sundry Disorders arising in the animal Ecomony from some foreign liquids being directly admitted into the Current of Blood; the Considerations made me, 1721, not enter into the Practice until further Trials did evince the Success of it.

Bulletin of The Society of Medical History of Chicago, Vol. II, April, 1921, No. 4, in Society of Medical History of Chicago, Bulletin of the Society of Medical History of Chicago, Volumes Two (Chicago, IL), 236.

Douglass’s change in position, however, does not disprove the dangers inherent in smallpox inoculation. People change positions all the time — sometimes for the worst (for whatever reason). If an anti-communist makes valid arguments against communism (e.g., showing it is a murderous ideology), but then later adopts communism, it does not disprove his initial arguments. Regarding Douglass, we have plenty of witnesses confirming his initial statements that smallpox inoculation is deadly — so many so that the practice would eventually be criminalized.

But if pro-vaxxers would nevertheless still insist here that change in views vindicates vaccination, they are confronted with the fact that countless people (including doctors) have changed their views against vaccination throughout vaccine history. Often, after they experience vaccine injury firsthand, or after their child is murdered by the procedure. So the matter of Dr. Douglas does nothing to vindicate vaccination — and to insist that it does is special pleading in the worst way.

Back to the deadliness of inoculation. On July 22, 1721, Boston physicians and surgeons testified to the dangers of smallpox inoculation:

At a meeting by publick authority in the Town House of Boston, before His Majesty’s Justices of the Peace and the Select Men ; the practitioners of physic and surgery being called before them, concerning Inoculation, agreed to the following conclusion : —

A Resolve upon a debate held by the physicians of Boston concerning inoculating the Smallpox on the 21st day of July, 1721 .

It appears by numerous instances, that it has proved the death of many persons soon after the operation, and brought distempers upon many others which have in the end proved deadly to them.

That the natural tendency of infusing such malignant filth in the mass of blood is to corrupt and putrefy it, and if there be not a sufficient discharge of that malignity by the place of incision, or elsewhere, it lays a foundation for many dangerous diseases.

That the operation tends to spread and continue the infection in a place longer than it might otherwise be.

That the continuing the operation among us is likely to prove of most dangerous consequence.

The number of persons, men, women, and children, that have died of smallpox at Boston from the middle of April last (being brought here then by the Saltertuda’s Fleet) to the 23rd of this instant July (being the hottest and worst season of the year to have any distemper in) are, viz. -2 men, strangers , 3 men, 3 young men, 2 women, 4 children, 1 negro man, and 1 Indian woman, 17 in all ; and of those that have had it, some are well recovered, and others in a hopeful and fair way of recovery.

BY THE SELECT MEN OF THE TOWN OF BOSTON.Cited by William White, The Story of a great delusion in a series of matter-of-fact chapters (London: E.W. Allen, 1885), 4, 5.

Smallpox inoculation shown to be counterproductive, spreading smallpox and death

Instead of halting smallpox epidemics, smallpox inoculation spread them — and much more. Inoculation was an igniter of disease and death.

As Duncan Neuhauser and Dr. Lee Slavin note, the person inoculated could not only die from smallpox, but also spread the disease to close contacts.

[Duncan Neuhauser, and Lee Slavin, “The Self-Evidence of Benjamin Franklin,” in Mark A. Best, Duncan Neuhauser, and Lee Slavin, Benjamin Franklin: Verification and Validation of the Scientific Process in Healthcare As Demonstrated by the Report of the Royal Commission on Animal Magnetism & Mesmerism (Trafford Publishing, 2003), 76.]

Rebecca Jo Tannenbaum writes,

Opponents were quite correct in seeing a danger to public health—one careless inoculation patient could trigger a major epidemic.

Rebecca Jo Tannenbaum, Health and Wellness in Colonial America (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2012), 96.

And Karen Walloch comments,

[I]noculation perpetuated smallpox as an endemic disease that occasionally broke out in epidemic form, when inoculated patients mingled too soon with their neighbors, especially in towns that had lax controls. One physician, writing in the nineteenth century, remarked that inoculation “spread smallpox just as the natural disease did” and “often with great virulence.” … An 1866 American Medical Association report explicitly linked the decrease of smallpox epidemics in the nineteenth century to the abandonment of inoculation … In 1871, British smallpox expert J. F. Marson testified before Parliament that “the discontinuance of inoculation, rather than the practice of vaccination, was the cause of the lesser prevalence of smallpox” from 1800-30.

Karen Walloch, “A Hot Bed of the Anti-vaccine Heresey”: Opposition to Compulsory Vaccination in Boston and Cambridge, 1890-1905 (Ann Arbor, MI: ProQuest, 2008), 25, 26.

Dr. James Martin Peebles, in Vaccination a Curse and a Menace to Personal Liberty: With Statistics Showing Its Dangers and Criminality (1913), writes,

After the fruitless trial of nearly a century, it was discovered that inocculation was sowing the seeds of a long train of diseases, in their most fatal form, communicating infectious complaints from one person to another—cancer, scrofula, consumption, and other more loathsome diseases were spreading to an alarming extent. It was seen and confessed by hundreds of physicians that the net result of this practice was a multiplication of ailments and an enormous increase in the total mortality. Dr. Winterburn, of Philadelphia, writes,—”The Value of Vaccination,” page 18:—

“From the most trustworthy sources, however, it is evident that just as now we have epidemics of measles, and other of the zymoses, varying greatly in intensity and fatality, so in the pre-inoculation period there were epidemics of small-pox of great fatality and others of very moderate intensity. But after the introduction of inoculation, the ravages of small-pox increased, not only directly as the result of inoculation, but each new case became, as it were, a centre of disease, from it spreading in every direction, often with great virulence. It spread small-pox just as the natural disease did. It could be propagated anywhere by sending in a letter a bit of cotton thread dipped in the variolous lymph. In this way, not only the number of cases, but, also, the general mortality was very greatly increased. But so hard is it to alter the ideas of a people after they have crystallized into habit, that although it was evident that epidemics of small-pox often started from an inoculated case; and although the most strenuous efforts were made to supersede it by vaccination, inoculation continued to flourish for nearly a century and a half. It was found necessary in 1840 to make inoculation in England, a penal offense, in order to put an end to its use. Even that has not prevented its secret practice by the lower orders, where ideas die hardest, and the rite is even now probably more than occasionally performed.”

James Martin Peebles, Vaccination a Curse and a Menace to Personal Liberty: With Statistics Showing Its Dangers and Criminality (Los Angeles, CA: Peebles Publishing Company, 1913), 16, 17.

Smallpox inoculation (in the form of variolation) criminalized

Writing in the 1800s, Professor Robert A. Gunn, M.D., Dean of the United States Medical College in New York, summarizes the rise and fall of inoculation in the form of variolation — from the initial zeal for it and its cultural acceptance, to its eventual official discrediting and criminalization:

Its advocates claimed that the ravages of small-pox were thus greatly diminished, and the profession and public, alike, worked zealously to promulgate the practice. After vaccination was introduced, it was ascertained that inoculation added greatly to the number of small-pox cases, and that the mortality was not diminished, but rather increased. Stringent laws were then passed, in different countries, making the practice of inoculation a crime.

Robert A. Gunn, Vaccination: Its Fallacies and Evils (New York: Nickles Publishing Company, 1882), 5.

In the 1800s, Arthur Wallaston Hutton, M. A., said that when the medical community wanted to replace inoculation with vaccines, they essentially “confessed” to the failures of the former:

In the early years of the present century, when medical men, with almost complete unanimity, were seeking to replace the variolous inoculation by the vaccine inoculation, they confessed, or rather urged, that the earlier practice had destroyed more lives than it had saved.[17]

Cited in Peebles, Vaccination a Curse and a Menace to Personal Liberty, 18.

Not that vaccination which replaced smallpox variolation was good either, as history shows; only that there was at least an admission to the dangers and failures of variolation. But the principle of blood poisoning (unwittingly) introduced by Mather continued.

Really the vaccinators gave with one hand and took with another. Just as smallpox variolation spread smallpox, so did smallpox vaccination. If in fact smallpox variolation spread smallpox on a greater scale, smallpox vaccination likely caused cancer on a greater scale. In any case, both caused widespread suffering and death.

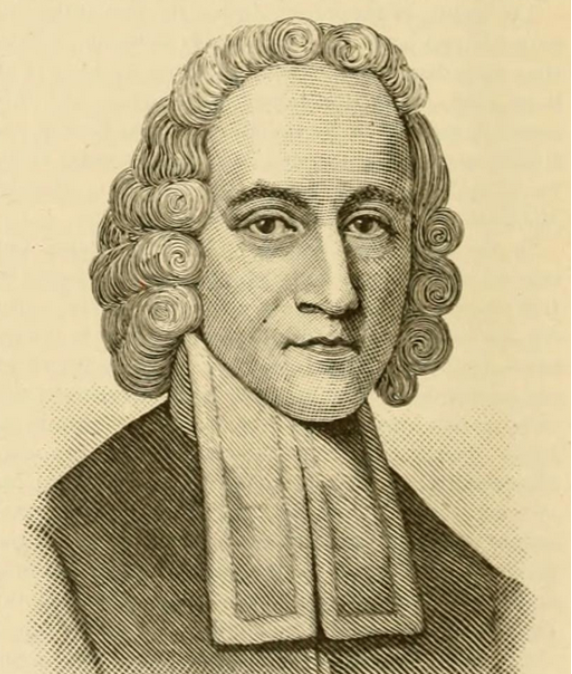

The tragedy of Jonathan Edwards

One of the most popular victims of smallpox inoculation was the famous Great Awakening Preacher Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758). Edwards got inoculated due to his doctor’s encouragement, and also wanted to set an example for others.

This was in New Jersey, almost forty years after the inoculation controversy began in Boston. The leaven of blood poisoning in the name of health was sweeping the nation. As was the fake news giving the idea that inoculation was a “safe and effective” procedure.

Sadly, Edwards didn’t heed the warnings to not undergo inoculation — and the results were disastrous (Christians — take it seriously when you are warned about vaccines!):

Edwards’ physician encouraged the inoculation, but others warned him not to take it. No doubt, He knew of the position taken by his colleague Cotton Mather. He advocated for the new vaccine … As a pastor, he urged his congregation and doctors to get inoculated. Edwards reasoned that his taking the vaccine would be an example to others and help save lives in the end. Within days, he was deathly sick and near death. … He died quietly from the vaccine and medication related complications that set in shortly after the injection. His death was related to his high fever and starvation from a prolonged period of not being able to swallow liquids and food.

Allan G. Hedberg, Jonathan Edwards: A Life Well Lived (Bloomington, IN: WestBow Press, 2016) (Google preview version: no page number given). Retrieved April 24, 2024, from https://books.google.com/books?id=xacADAAAQBAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

Besides causing a slow, agonizing death of starvation, the tragedy severely affected his whole family. His wife was left a widow and his children orphans.

Unexpectedly, the cure became the killer, and he died from the inoculation on March 22 at the age of fifty-four, leaving Sarah to raise their large family alone. It was the last and worst of a series of heavy calamities that had befallen Sarah. … Sarah would never recover from her loss.

Carolyn Custis James, When Life and Beliefs Collide (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2001). (Google preview version: no page number given). Retrieved March 16, 2015, from https://books.google.com/books?id=kuJh97T1t0cC&source=gbs_navlinks_s

While Edwards meant to set a positive example for undergoing inoculation, his horrific death only served as a cautionary tale against this procedure: it was shown to be suicidal. For Edwards, inoculation caused a slow, agonizing death; his wife was devastated and his family deprived of a husband and father; and the church was deprived of a great preacher.

Smallpox threat tended to be exaggerated

In Boston, just how bad was the supposed threat of smallpox that prompted the inoculation campaign in 1721? Hard to say. William White writes,

The precise truth as to the extent of the Boston epidemic is far from easy to ascertain : it was the temptation of the inoculators to magnify the numbers of the afflicted and of their antagonists to minimise. …

William White, The Story of a great delusion in a series of matter-of-fact chapters (London: E.W. Allen, 1885), 4.

But beyond this, there are some other considerations. Deaths attributed to smallpox can actually be due to other diseases. At least, Isaac Massey, an apothecary to Christ’s Hospital, says this about his experience in London:

These Bills [of Mortality] are founded on the ignorance or skill of old women, who are the searchers in every parish, and their reports (very often what they are bid to say) must necessarily be very erroneous. Many distempers which prove mortal, are mistaken for the smallpox, namely, scarlet and malignant fevers with eruptions, swinepox, measles, St. Anthony’s fire, and such like appearances, which if they destroy in three or four days (as frequently happeneth) the distemper can only be guessed at, yet is generally put down by the searchers as smallpox, especially if they are told the deceased never had them.

Letter to Dr. Jurin. London, 1723. Cited in William White, The Story of a great delusion in a series of matter-of-fact chapters (London: E.W. Allen, 1885), 26.

There is also the question of how many supposed smallpox deaths were actually due to the treatments. Death by treatment is very easy to conceal since the ailment being treated can be blamed instead. In the case of smallpox treatments, we have this from Rex U. Lloyd, cited in The Poisoned Needle: Suppressed Facts About Vaccination (1957).

If the death rate of smallpox and fevers was so enormous, it was largely due to the medical treatment of that time. … Dr. Russell T. Trall, the eminent Natural Hygienist, considered smallpox “as essentially . . not a dangerous disease.” He cared for large numbers of patients afflicted with smallpox and never lost a case. Under conventional medical treatment, patients were drugged heroically, bled profusely, were smothered in blankets, wallowed in dirty linen, were allowed no water, fresh air and stuffed with milk, brandy or wine. Antimony and Mercury were medicated in large doses. Physicians kept their patients bundled up warm in bed, with the room heated and doors and windows carefully closed, so that not a breath of fresh air could get in, and given freely large doses of drugs to induce sweating (Sudorifics), plus wine and aromatized liquors. Fever patients were put into vaporbath chambers in order to sweat the impurities out of the system. Given no water when they cried for it and when gasping for air were carried to a dry-hot room and after a while were returned to the steam torture. Many must have died of Heat Stroke!

VACCINATION—A MEDICAL DELUSION by Rex U. Lloyd. Cited in

Eleanor McBean, The Poisoned Needle: Suppressed Facts About Vaccination (1957, Whale, June 2002). Retrieved May 25, 2023, from http://www.whale.to/a/mcbean.html

Whether or not any of these specific treatments were used in Boston for smallpox in 1721, one must consider the role that doctors may have played then in their patients’ deaths’ in trying to cure smallpox.

Also, some interesting comments about Boston from William White:

Boston was an extremely unhealthy town. For fifty years, from 1701 to 1750, the births were exceeded by the deaths. In a population of about 15,000, the annual death rate ranged from 30 to 70 per thousand. There were epidemics of fever and of smallpox ; the latter occurring in general at intervals of ten years, when large numbers died, the smallpox as usual displacing other forms of fever, but nevertheless raising the mortality of the year.

William White, The Story of a great delusion in a series of matter-of-fact chapters (London: E.W. Allen, 1885), 371.

When we consider the unhealthy state of Boston, we can easily deduce that hygiene, sanitation, and nutrition — not a poisoned needle — could have averted many supposed smallpox deaths.

All of this to say that we must not be quick to believe a bad report about diseases — and then run headlong into a cure worse than the disease. Mather and his inoculators let panic override a calm, rational response to smallpox.

Vaccine deaths and denying the obvious: here from the outset

If you warn people about vaccines with solid evidence of vaccine-caused deaths, you probably repeatedly experience rejection of your evidence, not matter how much you give. You might even suspect such people have a suicide wish. Sadly, rejection of the obvious when it comes to vaccines is ubiquitous. And this kind of cognitive dissonance was here from the outset.

Like today, when harm follows vaccination, there was always an excuse in the early days of inoculation to protect it from reproach. Inoculation as a likely cause of harm or death was regularly dismissed for some other reason. In the cases discussed below, it was 1) diseases acquired prior to inoculation; 2) not being “sound” or “healthy” prior to inoculation; or 3) affliction from a condition that was “concealed” from the inoculator prior to inoculation.

Convenient coincidences; confirmation bias at its worst. As if other health conditions — to the extent they were actually there — cannot be made worse by inoculation! As if having other conditions disproves inoculation was actually the cause of one’s death! As if it is impossible that infecting someone’s blood with foreign substances could cause harm — especially when compared with catching illness the natural way!

Indeed — if someone with a health condition dies after being bitten by a venous snake, does that condition nullify the role the snake’s venom likely played in one’s death?! Vaccination/inoculation, by the way, is the bite of a venomous snake!

Regarding inoculation deaths and denying the obvious (whether inoculation as the obvious cause of death, or at least obvious likely cause of death), here are a couple instances with Cotton Mather himself. In addressing those who sickened or died after the procedure, he does provide explanations as to why he believes inoculation was not the cause. But his stubborn commitment to this procedure blinds him to the obvious likelihood (given that the procedure is extremely unnatural and thus against God’s created order) that the cause was indeed inoculation.

For instance, Mather expresses his unfounded confidence that those who died after inoculation actually died from something else:

I cannot learn that one has died of it ; though the experiment has been made under various and marvellous disadvantages. Five or six have died upon it, or after it , but from other diseases or accidents ; chiefly from having taken infection in the common way by inspiration before it could be given in this way by transplantation.

Dr. Leigh, in his Natural History of Lancashire, counts it an occurrence worth relating, that there were some catts known to catch the smallpox, and pass regularly through the state of it, and then to die. We have had among us the very same occurrence.

Cotton Mather, March 10, 1722. Cited in William White, The Story of a great delusion in a series of matter-of-fact chapters (London: E.W. Allen, 1885), 3.

Did Mather have proof that those who died actually had a disease? Moreover, even if they did, any scientifically-minded person would realize that it is possible that inoculation increased the severity of the disease. This doesn’t occur to Mather — and neither does the fact that between taking a disease the natural way and poisoning the blood with foreign substances, good sense tells us that the latter is much more likely to be the cause of death.

Mather ruling out the most obvious possible cause of death is a recurring theme we see in the vaccinators. William White comments,

Considering the developed evidence that awaits us as to the character and results of inoculation, it would be superfluous to discuss this singular report, but we may remark the consummate audacity with which Mather assumes and maintains his position.

Ibid., 4.

Mather didn’t learn from the near tragedy he suffered the year before, when his own son severely sickened — maybe almost died — after inoculation, which should have caused him to reconsider the procedure. Instead, he thought that his son’s suffering was simply due to smallpox acquired before the inoculation:

His son Samuel wished to be inoculated. … In the middle of the month, he yielded to Sam’s request, and the lad was inoculated. He sickened so fast and so severely that his father was seized with a dread that perhaps, before the inoculation, the poor boy had already contracted the disorder.

Barrett Wendell, Cotton Mather, the Puritan Priest (NY: Dodd, Mead, and Company, 1891), 277.

In Mather’s own words:

My dear Sammy, having received the Smallpox in the Way of Inoculation, is now under the Fever necessary to produce the Eruption. But I have Reason to fear, that he had also taken the Infection in the common Way; and he had likewise but one Insition, and one so small as to be hardly worthy the Name of one, made upon him. If he should miscarry, besides the Loss of so hopeful a Son, I should also suffer a prodigious Clamour and Hatred from an infuriated Mob, whom the Devil has inspired with a most hellish Rage, on this Occasion.

Massachusetts Historical Society Collections: Seventh Series–Vol. VIII, Diary of Cotton Mather, 1709-1724, “August, 1721” (Boston, MA: The Society, 1912), 638, 639.

Mather above says that his son was only inoculated with a very small incision — implying that he believes that it wasn’t enough to be dangerous or it wasn’t enough to be effective (or both). And yet, later Mather writes that it could have been enough to be effective:

The Condition of my Son Samuel is very singular. The Inoculation was very imperfectly performed, and scarce any more than attempted upon him; And yett for ought I know, it might be so much as to prove a Benefit unto him. He is however, endanger’d, by the ungoverned Fever that attends him.

Ibid., 641.

However, if the inoculation could have been effective, then it means that the inoculation could have successfully entered the bloodstream, with all of its poisons; meaning that the procedure could have also have been dangerous.

We also see the hubris and cognitive dissonance in Mather’s partner in inoculation, Dr. Zabdiel Boylston:

And as to those who died under Inoculation, I would observe that Mrs. Dixwell, we have great reason to believe, was infected before. Mr. White thro’ splenetic delusions, died rather from abstinence than the Small Pox. Mrs. Scarborough and the Indian girl died of accidents, by taking cold. Mrs. Wells and Searle were persons worn out with Age and Diseases, and very likely these two were infected before. Neither can it be said, that there was one sound and healthy person amongst them.

Zabdiel Boylston, An historical account of the small-pox inoculated in New England, upon all sorts of persons, whites, blacks, and of all ages and constitutions ; with some account of the nature of the infection in the natural and inoculated way, and their different effects on human bodies : with some short directions to the unexperienced in this method of practice (London: S. Chandler, 1730), iii.

With this kind of reasoning, any death by inoculation can be explained away.

But wherever the practice went, the hubris and cognitive dissonance followed, as we see in Boylston’s fellow proponent overseas, Dr. Charles Maitland. While Mather and Boylston introduced the procedure in New England, the physician Charles Maitland did so in England.

With Maitland, we again see a denial of the obvious. Here are a couple deaths where he arbitrarily dismisses any role inoculation could have played in them:

The second son of Lord Hillsborough, at the age of seven, was inoculated by Mr. Maitland, May 24th, 1725. “He sickened the third day, that is, four days sooner than the usual, and the eruption appeared the fifth day, neither did his disease observe the signs and course of the Small-pox by inoculation. Whereby it is plain he had taken the infection from his sister, who had the natural distemper in the family before he was inoculated. Upon the twentieth day after the operation, when the Small-pocks were dry and sealing off, he died of a most malignant fever, as was evident by the several exanthemata, which were seen on his body some days before his death.” Mr. Maitland. …

Mr. Urquart’s child, one year and an half old, was inoculated at Meldrum, in Aberdeenfhire, by Mr. Maitland, August 29th, 1726. “This boy sickened the seventh, and died on the eighth day, before any appearance of eruption, of fits (from a hydrocephalus), which he had formerly been subject to, though concealed both from the parents and the operator. ” Mr. Maitland.

William Woodville, The History of the Inoculation of the Small-Pox, in Great Britain; Comprehending a Review of All the Publications on the Subject: with an Experimental Inquiry Into the Relative Advantages of Every Measure which Has Been Deemed Necessary in the Process of Inoculation: Volumen One (London, James Phillips, 1796), 179-181.

The second of the deaths described above provoked an outcry against Maitland’s reckless procedure:

Maitland returned to Scotland, his native country, in 1726, and, going among his relations in Aberdeenshire, showed off his skill by inoculating six children. One of them, Adam, son of William Urquhart of Meldrum, aged 18 months, sickened on the seventh, and died on the eighth day. There was a great outcry, and Maitland tried to excuse himself by asserting that Adam was afflicted with hydrocephalus, which had been improperly concealed from him. Anyhow, the Aberdeenshire folk were satisfied with their experience, and recommended “Charlie Maitland to keep his new-fangled remedy for the English in future.” He was more fortunate in the west of Scotland, where he “inoculated four children of a noble family,” who escaped alive. The Scots, however, were deaf to his persuasions, and he made no headway among them. At a later date, 1733, inoculation began to be practised in and about Dumfries, and occasionally elsewhere.

William White, The Story of a Great Delusion in a Series of Matter-of-fact Chapters (London: E.W. Allen, 1885), 34.

A Biblical critique of inoculation

While sadly, pastors today generally do not condemn vaccination, they weren’t so silent during the plague of smallpox inoculation:

Many clergymen denounced the practice from their pulpits as immoral.

Francis Randolph Packard, The History of Medicine in the United States

(Philadelphia, PA: J.B. Lippincott, 1901), 79.

Back then, they had not yet been desensitized to a practice so obviously against God’s created order; neither was the practice so universally entrenched; nor was there an unrelenting propaganda campaign. Consciences were not yet seared on a titanic level.

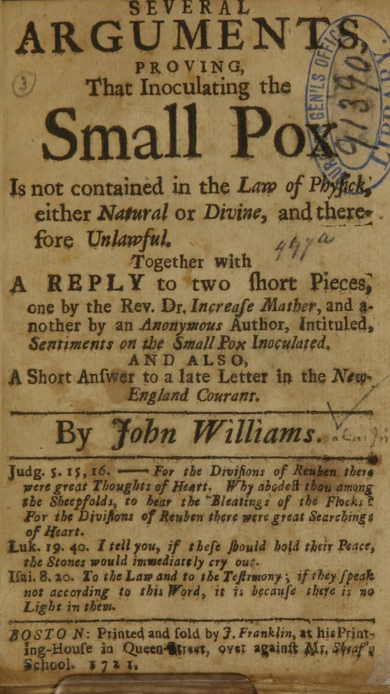

In any case, during the inoculation controversy, one pastor who was very outspoken against inoculation was the Reverend John Williams. Williams called inoculation

a Delusion of the Devil; and that there was never the like Delusion in New-England, since the Time of the Witchcraft at Salem, when so many innocent Persons lost their Lives … [6]

John Williams, An answer to a late pamphlet, intitled, A letter to a friend in the country, attempting a solution of the scruples and objections of a consciencious or religious nature, commonly made against the new way of receiving the small pox (Boston, MA: J. Franklin, 1722), 4.

The reason was because inoculation endangered the lives of its recipients; thus, Williams said it was a violation of God’s law:

They are guilty of the Breach of the Moral and the Evangelical Law of God; for they have not done by their Neighbour as they would that their Neighbour should do to them, and that in a Case of great Moment; not only to the hazard of Life, but the Loss of many a Life; how many God knows. Math. 7.12. Therefore all things whatsoever ye would that Men should do to you, do ye even so to them; for this is the Law and the Prophets.

If we are commanded to love our Neighbour as our selves, then they that voluntarily bring in the Small Pox into their House, and not only endanger their Neighbours Health and Life, but eventually take both away, do transgress the Law and the Prophets, Matt, 22, 35, 36, 27 [37?], 38, 39, 40. And, Oh! What a Fountain of Blood are the Promoters guilty of! God grant them repentance unto life. May it not be said of you, You lay aside the Commandments [of] God, and ye have learned the Traditions of Men. Mark. 7. 9. And he said unto them, Fulwell ye reject the Commandment of God, that ye may keep your own Tradition.[7]

[7] John Williams, Several arguments proving, that inoculating the small pox is not contained in the law of physick, either natural or divine, and therefore unlawful: together with a reply to two short pieces, one by the Rev. Dr. Increase Mather, and another by an anonymous author, entitled, Sentiments on the small pox inoculated ; and also, a short answer to a late letter in the New England Courant. (Boston, MA: J. Franklin, 1721), 3, 4.

In a letter to the New-England Courant, a one Frank Scammony raises the matter of moral responsibility for deaths resulting from inoculation, and argues from Scripture against it:

If Infection is communicated to another by means of Self-Infection, and this Contagion spreads itself among others, and any of these thus infected perish, at whose hands shall their Blood be required? Since it was probable they might have escaped the Natural Pock when they fell by means of the Inoculated Pock, and thereby come to an untimely End. . .

In short, I affirm it unlawful for a Person in Health upon any Account [for any reason] to receive a less Infection to avoid a greater, because Our blessed Saviour, the Great, the Skillful Physician says, He that is whole needs not a Physician, but he that is Sick. He allows of Application to Physicians in Cases of Illness, but Health has no need of Recourse to them.

Frank Scammony, The New-England Courant, August 21-28, 1721. Cited in National Humanities Center, The Paper War over Smallpox Vaccination in Boston, 1721, 4.

While Reverend John Williams was a leading voice against smallpox inoculation in America, Reverend Edmund Massey was a leading voice against it in England. In 1722, Massey said to the leading inoculater of England, Dr. Maitland, that inoculation calls evil good, and good evil:

Till you shew me how these Contradictions can be reconciled, and a necessary Practice be drawn into Precedent to warrant an Unnecessary One, you must excuse me that I take you to be of the Number of those who call Evil Good, and Good Evil; who put Darkness for Light, and Light for Darkness; who put Bitterness for Sweet, and Sweet for Bitter; Isa. v. 20. against whom the Prophet has denounced a Wo!

Reverend Edmund Massey, A Letter to Mr. Maitland in Vindication of the Sermon Against Inoculation. (Norwich: S. Mascott), 22. (Not mentioned in this version itself, but it was printed in 1722.)

Elsewhere, Massey calls inoculation presumption before God:

It is written, Thou shalt not tempt the Lord thy God: This was our Saviour’s Answer to the Devil, when he would have persuaded him to the Commission of a presumptuous Action. There are Angels, says the Tempter, to take Care of you, so that you cannot possibly come to any Harm, then make the Experiment, and cast thy self down. Now there is no great Difference between this of the Devil, and the Temptation which lies before us ; both intimate the Safety of the Practice, and both pretend the Blessing of God : Our Lord’s Reproof then will serve them both : No, says he, we must not presume upon God’s Protection, to expose our selves to any unnecessary Danger or Difficulty. If Trials overtake us, he to whom we pray not to lead us into Temptation, will make a Way for us, that we may be able to bear them : But if we overtake them, if we seek for a Disease, and so lead our selves into Temptation, we can have no rational Dependance upon God’s Blessing: It is with Difficulty we can sanctify our Afflictions in the Course of Providence, in the Way of our Duty, and ’tis odds but we miscarry under them, when we bring them upon our selves: If God’s Blessing be withdrawn, it must unavoidably be so ; and such Circumstances wherein we have no Reason to expect his Blessing, are, I think, by no means to be run into.

Reverend Edmund Massey in Mr. Boyer, ed., The Political State of Great Britain for the Month of August, 1722. (London: T. WARNE), 119.

About 30 years later, Theodore Delafaye of Canterbury, an Anglican clergyman, preached a sermon against inoculation on June 3, 1753. Here he considered inoculation as doing evil that good may come.

As William White writes, he preached

from the text, ‘Let us do evil that good may come’ (Rom. iii. 8), and published it under the title of Inoculation an Indefensible Practice.

William White, The Story of a Great Delusion in a Series of Matter-of-fact Chapters (London: E.W. Allen, 1885), 42.

In short, inoculation/vaccination is harming someone in the name of preventing a future harm; a violation of the Sixth Commandment in the name of preserving it.

practice of inoculation “a Delusion of the

Devil; and that there was never the like

Delusion in New-England, since the Time

of the Witchcraft at Salem, when so many

innocent Persons lost their Lives.”

Inoculation fosters mistrust of the clergy

Evils tend to lead to other evils. In the case of inoculation — which was an evil, murderous practice (even if its proponents did not discern it to be so) — the clergy who promoted it overstepped their bounds and hurt their credibility. People often distrusted those who promoted it. The inoculation controversy stimulated

anti-ministerial feeling in Boston — and probably in nearby communities as well. There is, of course, no way of measuring how pervasive this feeling was in the society. Its bitterness, however, appeared unmistakable; and the evidence of popular attitudes — from the anger of the Courant to the melancholy defenses of ministers in the Mather group — suggests it was widespread.

Robert Middlekauff, The Mathers: Three Generations of Puritan Intellectuals: 1596-1728 (London: Oxford University Press, 1871), 358.

I have heard people speak of their frustration of pastors promoting vaccination. I wonder, how many have even abandoned meeting with the church completely over the distrust fostered by this? I strongly urge those who have done so to find a biblical church to meet with — it is not spiritually healthy to forsake assembling with the saints. But I strongly urge pastors to refrain from promoting vaccines; to consider the harm they are doing, both physically (to those who take their advice), as well as spiritually, to those they may be provoking to abandon church fellowship.

When vaccine harm comes: calling out to God

To his credit, Cotton Mather cried out to God to heal his son who may have come close to death after being inoculated:

It is a very critical Time with me, a Time of unspeakable Trouble and Anguish. My dear Sammy, has this Week had a dangerous and threatening Fever come upon him, which is beyond what the Inoculation of the Small-Pox has hitherto brought upon any Subjects of it. In this Distress, I have cried unto the Lord ; and He has answered with a Measure of Restraint upon the Fever. … I sett apart this Day, for Supplications to my glorious Lord, on this distressing Occasion. … I beg’d for the Life of the Child, that he may live to serve the Kingdome of GOD, and that the Cup which I fear, may pass from me.

Massachusetts Historical Society Collections: Seventh Series–Vol. VIII, Diary of Cotton Mather, 1709-1724, “August, 1721” (Boston, MA: The Society, 1912), 639, 640.

Thankfully, Mather’s son survived. God healed him. Let this be an example to Christians who suffer, or whose children suffer, from vaccines — cry out to God, Who may decide, in His perfect wisdom, to restrain the ill effects of vaccination.

Concluding thoughts

As the saying goes, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” As Christians, we need to be humble and learn from the mistakes and sins of the past. However unwittingly, we have a fountain of blood on our hands for introducing and popularizing the blood-poisoning procedure of inoculation/vaccination throughout the world.

Let the tragedy of Cotton Mather instruct us. When we don’t take care to consider God’s natural order, and what may be violations of His law, we are inviting disorder and death. Like gravity, God’s order cannot be violated without consequences. And regarding inoculation/vaccination, to this day we have reaped severe consequences on a titanic scale.

An essential ingredient in vaccine genocide is a rejection of wise counsel. Mather refused the counsel of the physicians and others who saw inoculation for the natural and moral outrage that it was. To this day, you can warn others — even fellow Christians — about vaccines with irrefutable evidence, but many will not listen; although some do wake up when they are injured or their child dies from vaccination. But it shouldn’t take a tragedy to accept the truth. We must not disregard wise counsel (Proverbs 15:22, 20:18).

At the same time, we must be careful to avoid the counsel of the misguided and of the wicked (Psalm 1:1). There are those who promote vaccines who have a zeal without knowledge. There are also very evil men who promote vaccines for personal monetary gain at best, or a lust to murder at worst. Exercise caution in trusting in institutions that have shown repeatedly to be opposed to Christ. Let us not hastily believe a bad report, calling us to rush headlong into vaccine poison to avoid a “virus that will kill us all.”

The sin of inoculation/vaccination carries with it a host of plagues: not only injury and death, but it sows distrust and division, results in widows and orphans, robs the church of spiritual gifts by the loss of its members, and hurts the church’s witness.

And so we must not continue to repeat the tragedy initiated unwittingly by Cotton Mather. Instead, we must repent of vaccination — and church leadership must publicly speak against it. We must do the opposite of what Mather and his followers initiated in New England — replace a zeal without knowledge with a zeal with knowledge.

In the meantime, as the church deals with current vaccine injuries, let us, like Cotton Mather, cry out to the Lord for help.

If you find this site helpful, please consider supporting our work.

Thank you for this insightful article.

Jen,

You’re welcome! Glad it was helpful.

Soli Deo Gloria.