What better way to drive you into the syringe of a deadly vaccine, than to paralyze you with irrational fear that invisible, murderous germs are everywhere — just waiting to snuff you out?

Disease hype and vaccination go hand-in-hand. Vaccination is built on a foundation of lies, and disease hype is a foundational plank. They used disease hype with polio and with COVID — and even from the beginning of the vaccine craze with smallpox.

Here we will touch on smallpox, which set the standard for subsequent vaccine narratives.

First, as we have previously discussed, many smallpox “fatalities” may have often been the result of smallpox treatments.

And if that wasn’t enough to overhype the dangers of smallpox, smallpox inoculation/variolation would spread smallpox, as would the vaccine itself after that — endlessly perpetuating smallpox vaccine mania.

But even then, there were other ways smallpox was overhyped: fallacious diagnoses and overstating of deaths, as well as the neglect of focusing on the crucial impact that poor hygiene, sanitation, and living conditions make (as if smallpox would affect you the same regardless of such factors).

These are just more areas that would foster an exaggerated sense of danger, making people desperate for a cure that would be worse than the disease. Below we will draw from a couple sources discussing these areas, as well as the aforementioned problem of dangerous smallpox treatments that would also exaggerate the perception of imminent smallpox danger.

Alexander Wheeler, in his 1878 book Vaccination in the Light of History, writes:

I have said that about this time [in earlier history] the small-pox begins to emerge from the classification of pest or plague, and is distinctly and specially noted and treated of. This was due to the revival of learning. For hundreds of years men had been more or less sufferers by it in Europe, and had failed to understand its treatment. “For centuries the practice of medicine in those countries best known to us was principally in the hands of persons whose healing resources were mainly drawn from magical arts and astrological superstitions.” The most loathsome drinks were gravely administered by learned men, and the vilest cruelty inflicted in the name of medicine. …

The patient was placed in just the reverse of suitable conditions and under the worst possible treatment, and yet we do not find the disease always present. A great writer like Fernel never alludes to it; another thinks every one must have it. The disease was present in epidemics, and absent for years together.

Alexander Wheeler, Vaccination in the Light of History (London: F. Pitman, 1878), 5, 6.

Wheeler further discusses the difficulty determining smallpox prevalence; there was also the problem of properly classifying smallpox, as another disease might be confused with it (the example he gives is measles, which, incidentally, may have in earlier times been more severe than today due to bad hygiene, nutrition, and treatment methods):

As to the actual prevalence of small-pox, it is by no means easy to state it. Imagine the epidemic of measles which of late visited and ravaged Fiji to have occurred in the times prior to Sydenham, and it would be recorded with small-pox, and doubtless modern writers would point to it as a solemn warning to anti-vaccinators. The two diseases were classed together. Further, the tables of mortalities are almost unavoidably for special years only. When a more than usually distinctive epidemic raged it was noted. But in general no attempt was made to get at the prevalence of any disorder.

Wheeler, Vaccination in the Light of History, 6.

Further hyping the death rate could have been the overstating of supposed smallpox deaths in relation to birthrates:

The old mortality tables were compiled from the parish burials; and the births are got from the baptisms. I opine that then, as now, great numbers of children grew up without baptism, but few would die without “Christian burial.” This would have the effect of making the death-rate appear excessive, when in reality the returns were untrustworthy and the death-rate moderate. Yet the gravest arguments are built upon these figures, which go to show that England would in a comparatively few years have seen its last man, so many more die than are born. No pretensions to accuracy of registration were made; and all calculations based on the old mortality returns, when compared with our registration statistics, are worse than valueless — they are positively misleading.

Wheeler, Vaccination in the Light of History, 6, 7.

Wheeler summarizes:

In truth, the extraordinary mortalities of small-pox which are so often quoted for times long distant from our own are only ‘founded on fact.’ They are not obtained from the actual records of experience. The assertions of Jurin, Lettsom, and others as to millions of lives being lost annually in Europe are wholly fallacious. No basis for such statements exist, or have existed. …

Yet the bold and presumptuous guesses and random assertions thus heaped together are even now passed on to ignorant people as giving the statistical fact as to small-pox in Europe one hundred years ago.

Wheeler, Vaccination in the Light of History, 12.

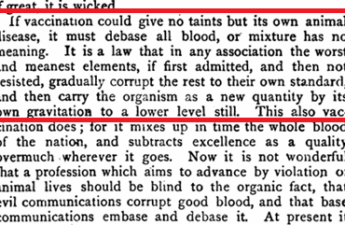

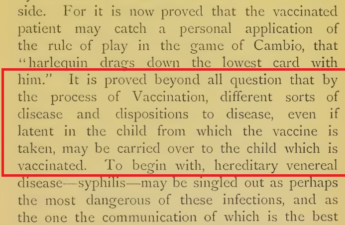

For more, we turn to William White’s The Story of a Great Delusion in a Series of Matter-of-fact Chapters in 1885. White writes:

Of course the Bills of Mortality were appealed to in evidence of the extent and fatality of smallpox; and as it is matter of common belief that prior to inoculation and Jenner (there is always a haze about the date) people were mown down with smallpox, it may be worth while reviving the table of relative mortality in London during the first twenty-two years of the 18th century.

William White, The Story of a Great Delusion in a Series of Matter-of-fact Chapters (London: E. W. Allen, 1885), 24.

White points out the fallacy of universalizing the dangers of smallpox that were unique to London — which itself would naturally foster disease, not owing to lack of vaccination, but due to poor hygiene and sanitation:

This large induction from London to universal mankind is noteworthy, because, as we shall see, it came to be often made, and involved a serious fallacy; for unless universal mankind dwelt in conditions similar to Londoners, it was idle to infer a common rate of disease and mortality. The population of London in 1701 was estimated at about 500,000 (there was no exact census), rising to about 600,000 in 1720. It was closely packed and lodged over cess-pools; the water supply was insufficient, and there was no effective drainage. The vast multitude was disposed, as if by design, for the generation and propagation of zymotic disease, and specially smallpox. Little attention was paid to personal cleanliness, and still less to ventilation, to light, to exercise. The condition of a large urban community a century ago is almost inconceivable at the present day.

Londoners were then only slowly and blindly rising out of those modes of existence which made the Plague of 1665, and other plagues, possible. Hence we need not be astonished that smallpox was a common and persistent affliction; but it was less prevalent and less deadly than it is the custom to assert; and had the disease not been attended with injury to feminine beauty, there might have been no more fuss made about it than about any other form of eruptive fever.

White, The Story of a Great Delusion in a Series of Matter-of-fact Chapters, 25, 26.

White adds that smallpox deaths could have been “much exaggerated” as a cause of death, due to confusing smallpox with other ailments:

It has also to be observed, that smallpox as a cause of death was probably much exaggerated in the Bills of Mortality; for as Isaac Massey pointed out —

“These Bills are founded on the ignorance or skill of old women, who are the searchers in every parish, and their reports (very often what they are bid to say) must necessarily be very erroneous. Many distempers which prove mortal, are mistaken for the smallpox, namely, scarlet and malignant fevers with eruptions, swinepox, measles, St. Anthony’s fire, and such like appearances, which if they destroy in three or four days (as frequently happeneth) the distemper can only be guessed at, yet is generally put down by the searchers as smallpox, especially if they are told the deceased never had them.” [Letter to Dr. Jurin, London, 1723]

White, The Story of a Great Delusion in a Series of Matter-of-fact Chapters, 26.

As White continues, poor living standards make a huge difference when it comes to the effect of disease:

Massey, in the same spirit of good sense, objected to generalisations about smallpox from the Bills of Mortality, as if all who died were slain by the disease and by nothing else.

“There ought to be no comparison [he said] between sick people, well regimented with diet and medicine, and those who have no assistance, or scarcely the necessaries of life.

“The miserable poor and parish children make up a great part, at least one-half of the Bills of Mortality; to confirm this I have examined several yearly bills, and I find that the out-parishes generally bury more than the ninety-seven parishes within the walls, and the parish of Stepney singly, very near as many as the City of London yearly; this sufficiently shows what little help and care are taken of the poor sick, which so much abound in all those places.” [Letter to Dr. Jurin, London, 1723]

White, The Story of a Great Delusion in a Series of Matter-of-fact Chapters, 26.

Pro-inoculation propaganda, however, did not give this significant difference much focus (a difference which would highlight the need for a healthy living standard instead of poisoning the blood):

Of course there lurks a fallacy in all statistics of disease wherein conditions of life are not discriminated. Whether patients survive or die from any zymotic ailment depends upon their breed, their circumstances, their habits, and their medical treatment and nursing — all essential particulars, yet difficult to define and register on a large scale. It would appear that in sound constitutions, and with fair treatment, smallpox in 1721 was by no means deadly, whilst in bad constitutions, and with exposure and neglect, it was extensively fatal. Yet of these differences, little account was taken by the Inoculators, and the malady was measured and discussed as though it were something uniform like water or gold.

White, The Story of a Great Delusion in a Series of Matter-of-fact Chapters, 26, 27.

If you find this site helpful, please consider supporting our work.