(image source)

“Keep your tongue from evil and your lips from speaking deceit.” (Psalm 34:13)

“Unequal weights and unequal measures are both alike an abomination to the Lord.”(Proverbs 20:10)

“You shall not murder.” (Exodus 20:13)

“learn to do good; seek justice, correct oppression; bring justice to the fatherless, plead the widow’s cause.” (Isaiah 1:17)

“In 1807, Mr. Birch warned medical men to open their eyes and recognize the “evil results” of vaccination. In 1810, Dr. Maclean told us that it is incumbent on vaccinators to come forward to disprove the evidence against vaccination. Today adverse events are rarely reported.” — Jennifer Craig [1]

“In 1955, right after the [polio] vaccination program got under way, they radically redefined the diagnostic parameters of polio, followed soon thereafter by changes in labeling protocol, then by even more stringent technical requirements for a polio diagnosis. In short, they ultimately redefined not the disease, but the label, out of existence. That’s not disease eradication, that’s a con game.” — Shawn Siegel [2]

“In mass vaccination programs it is common practice to omit or ignore such information in presenting the case for vaccination to the public. There is a tendency to let the “experts” make the decisions, after which they summarize the evidence with such press release statements as ‘absolutely safe,’ and other statements designed not to educate, but to inspire absolute confidence.” — Clinton R. Miller, 1962, before the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce House of Representatives (7 years after the polio vaccine program began) [3]

by Steve C. Halbrook

posts in this series:

part 1: The Inoculation Controversy of the 1700s

part 2: Opposition to Vaccines by Doctors and Others in History

part 3: The Inquisition Against Opponents of Bad Medical Practices

part 4: The Medical Profession’s Legacy of Tyranny, Torture, and Murder

part 5: God’s Sovereign Control Over Diseases

part 6: Unsafe & Deceptive — the Polio Vaccine Scam

part 7: Moral Objections to Vaccination and Inoculation in History

part 8: Death Certificates and Hiding the Vaccine Holocaust

part 9: in progress

Series Intro

Vaccines have become one of the most polarizing issues of the day. There is an aggressive push by lawmakers to force everyone to become vaccinated, as well as intense hostility by many vaccine supporters towards those who question the efficacy and safety of vaccines.

Where’s all the opposition to vaccines coming from? Are opponents of them crazed fanatics, looking for a conspiracy, or are their concerns legitimate? Having given this topic much reflection and research, we are of the view that they indeed have a case against vaccines, and that vaccines—far from being safe and effective—are a dangerous plague and one of the greatest deceptions in our day.

This series is a case against vaccines from both an historical and biblical perspective. Our hope is that it will equip Christians to better understand how dangerous vaccines really are, and to approach the situation from a biblical worldview.

One of the most entrenched beliefs in our society is that polio vaccines eradicated polio, which had people living in a constant state of terror. The following quote from social commentator Thomas Sowell captures this belief:

It is hard to convey to today’s generation the fear that the paralyzing disease of polio inspired, until vaccines put an abrupt end to its long reign of terror in the 1950s.[4]

The belief of the polio vaccine’s success is repeatedly reinforced by our institutions. For instance, as stated on our trusted CDC’s website:

Following the widespread use of poliovirus vaccine in the mid-1950s, the incidence of poliomyelitis declined rapidly in many industrialized countries. In the United States, the number of cases of paralytic poliomyelitis reported annually declined from more than 20,000 cases in 1952 to fewer than 100 cases in the mid-1960s. The last documented indigenous transmission of wild poliovirus in the United States was in 1979.[5]

Now, many “know” that polio vaccines eradicated polio, but proving such is a different matter entirely. Vaccines, as vaccine researcher Shawn Siegel regularly points out, are a matter of trust — with our information being spoon-fed to us by those whom we know (or should know) not to blindly trust (e.g., bureaucracies, media, and academia).

The idea that vaccines eradicated polio is foundational to the pro-vaccine paradigm; it provides a basis for doctors (many of whom are sincere) to manipulate parents into vaccinating their children.

But, what if all of this is a con game — to the detriment of your health and those in your family? Certainly you can not rule it out at the outset; it is not as if you have ever been given slam-dunk evidence that vaccines did indeed eradicate polio (and safely, at that).

Like many things in life, we are raised to believe certain things as true that are really not. In a fallen world, falsehoods are easily entrenched in society. Since we are fallen and finite, lies and ignorance abound. Satan, the father of lies (John 8:44), has domination over the unconverted (Ephesians 2:2), who walk in the futility of their minds (Ephesians 4:17). And even the converted are not immune to embracing falsehood.

In short, traditions of men based on falsehoods — which Jesus had to correct during His earthly ministry — continue to this day. Fallen human nature has not changed.

Indeed, not everything we are told is a historical fact is indeed one — as anyone who seriously researches history or understands human nature knows.

And it is not as if the effectiveness of vaccination is self-evident. The idea is that by exposing someone to a disease via vaccination, that something like natural immunity can be acquired. However, injecting diseased matter directly into the bloodstream is not analogous to how one naturally acquires disease. (Just as the fatal process of injecting air into the bloodstream is not analogous to inhaling air.)

When one naturally acquires a disease, the disease does not directly enter the bloodstream, but goes through certain bodily processes first. But by going directly into the bloodstream, vaccination bypasses the innate immune system; vaccination is simply not analogous to natural immunity. (If oral vaccination is more analogous, there has been, nevertheless, serious problems with the oral polio vaccine, as we discuss.)

Not only this, but it is not self-evident that vaccines are safe — and in fact, experience tells us that they are most unsafe.

Thus, the notion that polio vaccines safely and effectively eradicated polio cannot be said to be self-evident; polio vaccine effectiveness is a matter of trust in what we are told. We will now show just how misguided that trust is, and in the process, show the vaccine paradigm — which employs the supposed success of the polio vaccine as a foundational argument — to be built on a house of cards.

Sections include:

1) What is Polio, How Does it Spread, and How Prevalent was it Before the Vaccine?

2) Vaccines Contribute to the Spread of Polio

3) Is Vaccination the Only Explanation for the Decline of Polio?

4) Don’t Blindly Follow Statistics (even those in support of Vaccines)

5) “Polio” Conveniently Redefined Following the Release of the Vaccine

6) Pro-Polio Vaccine Bias From the Outset: Clouding Objectivity, Stifling Opposition

7) Challenges to Polio Vaccine Efficacy

8) Polio Vaccine Deadly, and Spreads Polio

9) Statements by Major Polio Vaccine Scientists, SV40, and AIDS

10) Did your Doctor Show you the Polio Vaccine Package Insert Before Vaccinating you or your Child?

Note: footnotes are not included at the end of the entire article, but at the end of each section.

Notes

_____________________________________________________

[1] Jennifer Craig, History Repeats Itself: Lessons Vaccinators Refuse to Learn (International Medical Council on Vaccination, November 17, 2011). Retrieved May 7, 2015, from http://www.vaccinationcouncil.org/2012/04/17/history-repeats-itself-lessons-the-vaccinationists-refuse-to-learn-by-jennifer-craig-phd.

[2] Shawn Siegel, The Nature of the Beast (International Medical Council on Vaccination,October 28, 2014). Retrieved February 13, 2017, from http://www.vaccinationcouncil.org/2014/10/28/the-nature-of-the-beast-by-shawn-siegel/.

[3] Clinton R. Miller, “Statement of Clinton R. Miller, Assistant to the President, National Health Federation, Washington, D.C.” (Intensive Immunization Programs, May 15th and 16th, 1962. Hearings before the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce House of Representatives, 87th congress, second session on H.R. 10541), 86. Retrieved February 15, 2017, from http://www.whale.to/v/greenberg1.pdf.

[4] Thomas Sowell, Farewell (Townhall, Dec 27, 2016). Retrieved February 8, 2017, from http://townhall.com/columnists/thomassowell/2016/12/27/farewell-n2263649. [5] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases: The Pink Book Home, Poliomyelitis. Retrieved January 18, 2017, from https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/polio.html.

Polio was relatively rare — and especially so

in its paralyzing form.

What is Polio, How Does it Spread, and How Prevalent was it Before the Vaccine?

Neil Z. Miller, medical research journalist, writes in the Vaccine Safety Manual:

Polio is a contagious disease caused by an intestinal virus that may attack nerve cells of the brain and spinal cord. Symptoms include fever, headache, sore throat, and vomiting. Some victims develop neurological complications, including stiffness of the neck and back, weak muscles, pain in the joints, and paralysis of one or more limbs or respiratory muscles. In severe cases it may be fatal, due to respiratory paralysis.[1]

On how polio spreads, Miller writes:

Polio can be spread through contact with contaminated feces (for example, by changing an infected baby’s diapers) or through airborne droplets, in food, or in water. The virus enters the body by nose or mouth, then travels to the intestines where it incubates. Next, it enters the bloodstream where “anti-polio” antibodies are produced. In most cases, this stops the progression of the virus and the individual gains permanent immunity against the disease.

Many people mistakenly believe that anyone who contracts polio will become paralyzed or die. However, in most infections caused by polio there are few distinctive symptoms. In fact, 95 percent of everyone who is exposed to the natural polio virus won’t exhibit any symptoms, even under epidemic conditions. About 5 percent of infected people will experience mild symptoms, such as a sore throat, stiff neck, headache, and fever—often diagnosed as a cold or flu. Muscular paralysis has been estimated to occur in about one of every 1,000 people who contract the disease. This has lead some scientific researchers to conclude that the small percentage of people who do develop paralytic polio may be anatomically susceptible to the disease. The vast remainder of the population may be naturally immune to the polio virus.[2]

A strong case has been made that poliomyelitis is not in fact a contagious disease, but a result of poisoning. In a 1952 piece published in the Archive Of Pediatrics titled “The Poison Cause of Poliomyelitis And Obstructions To Its Investigation” (Statement prepared for the Select Committee to Investigate the Use of Chemicals in Food Products, United States House of Representatives), Dr. Ralph R. Scobey makes a thorough case for this. Some excerpts:

The disease that we now know as poliomyelitis was not designated as such until about the middle of the 19th Century. Prior to that, it was designated by many different names at various times and in different localities. The simple designations, paralysis, palsy and apoplexy, were some of the earliest names applied to what is now called poliomyelitis.

Paralysis, resulting from poisoning, has probably been known since the time of Hippocrates (460-437 B.C.), Boerhaave, Germany, (1765) stated: “We frequently find persons rendered paralytic by exposing themselves imprudently to quicksilver, dispersed into vapors by the fire, as gilders, chemists, miners, etc., and perhaps there are other poisons, which may produce the same disease, even externally applied.” In 1824, Cooke, England, stated: “Among the exciting causes of the partial palsies we may reckon the poison of certain mineral substances, particularly of quick silver, arsenic, and lead. The fumes of these metals or the receptance of them in solution into the stomach, have often causes paralysis.” …

In the spring of 1930, there occurred in Ohio, Kentucky, Alabama, Mississippi and other states an epidemic of paralysis. The patients gave a history of drinking commercial extract of ginger. It is estimated that at the height of the epidemic there were 500 cases in Cincinnati district alone. The cause of the paralysis was subsequently shown to be triorthocresyl phosphate in a spurious Jamaica ginger. Death resulted not infrequently from respiratory paralysis similar to the bulbar paralysis deaths in poliomyelitis. On pathological examination, the anterior horn cells of the spinal cord in these cases showed lesions similar to those of poliomyelitis.

These incidents show that epidemics of poisoning occur and furthermore, that epidemic diseases do not always indicate that they are caused by infectious agents. …

In 1936, during a campaign to eliminate yaws in Western Samoa by the injection of arsenicals, an epidemic of poliomyelitis appeared simultaneously. In one community all of the patients developed paralysis in the same lower limbs and buttocks in which they had received the injections and this pattern was repeated in 37 other villages, whereas there was no paralysis in uninoculated districts. The natives accused the injections as the cause of the epidemic of poliomyelitis. Most of the cases of paralysis occurred one to two weeks after the injection of the arsenic …

Dr. Robert W. Lovett of the Massachusetts State Board of health (1908), describing the epidemic of poliomyelitis in Massachusetts in 1907, and after reviewing the medical literature on experimental poliomyelitis, states: “The injection experiments prove that certain metallic poisons, bacteria and toxins have a selective action on the motor cells of the anterior cornua when present in the general circulation; that the paralysis of this type may be largely unilateral; that the posterior limbs are always more affected than the anterior; and that the lesions in the cord in such cases do not differ from those in anterior poliomyelitis.” It appears to be of great importance that various poisons, lead, arsenic, mercury, cyanide, etc., found capable of causing paralysis are employed in relation to articles of food that are used for human consumption. …

Toomey and August (1932) pointed out that some authors thought that poliomyelitis is a disease of gastrointestinal origin which might follow the ingestion of foodstuffs. In 193360, they noted that the epidemic peak of poliomyelitis corresponds with the harvest peak of perishable fruits and vegetables. They called attention to the fact that the disease occurs only in those countries which raise the same type of agricultural products. Dr. C.W. Burhans, one of the colleagues of the authors, thought that green apples might be a factor in the etiology of poliomyelitis. Toomey et al. (1943) points out that there is frequently a history of dietary indiscretions previous to an attack of poliomyelitis. They suspected that a virus could be found on or in unwashed fruit or in well water during epidemics of poliomyelitis. …

Since 1908 — for 44 years — poliomyelitis research has been predominantly directed along only one line of investigation, i.e., the infectious theory. This single line of study, precluding other possibilities, including the poison cause of the disease, has resulted from two factors, (1) The Public Health Law, and (2) the insistence, based entirely on animal experiments, that poliomyelitis is caused by a virus. …

1. The Public Health Law. The inclusion of poliomyelitis in the Public Health Law as a communicable, infectious disease dates back to the early part of the 20th Century. At that time many diseases, now known to be neither communicable nor infectious, were considered to be caused by an infectious agent simply because they occurred in epidemics. The general attitude of that period is expressed by Sachs (1911) in his statement: “In general, the epidemic occurrence of any disease is sufficient to prove its infectious or contagious character.” The vitamin deficiency diseases, beriberi and pellagra, are outstanding examples of epidemic diseases that were formerly considered to be infectious and communicable according to the logic employed by Sachs.[3]

(Read the full text here.)

If this doesn’t conclusively prove that poliomyelitis is a non-contagious disease caused by poisoning, it at least shows that cases of poisoning would have been misdiagnosed as polio (perhaps very frequently), — increasing the unwarranted panic about a polio “reign of terror.” Indeed, according to Suzanne Humphries, MD, and Roman Bystrianyk, a researcher of diseases and vaccines, DDT could induce identical symptoms to polio:

In the fear-baked summers of polio, many parents were totally unaware that exposure to DDT alone induced symptoms that were completely indistinguishable from poliomyelitis — even in the absence of a virus.[4]

Humphries and Bystrianyk note also that polio was never as rampant as is now believed. In Dissolving Illusions: Disease, Vaccines, and the Forgotten History, they write:

Since the early 1900s, we have been indoctrinated to believe that polio was a highly prevalent and contagious disease. … [see graph on page 8 here]

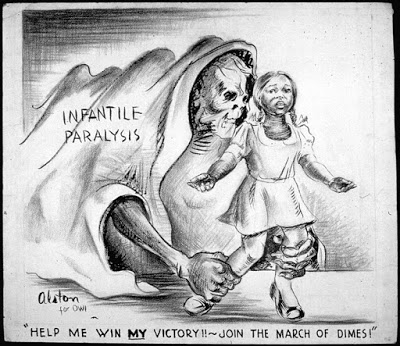

Given what a low-incidence disease it was, how did polio come to be perceived as such an infamous monster? This is a question worthy of consideration, especially in light of the fact that the rate was far less than other common diseases, some of which declined in incidence to nearly zero with no vaccine at all. Those who still embody a fear of polio may argue that polio was a monster because it crippled people, especially children. But it was later revealed, after a vaccine was lauded for the eradication of polio, that much of the crippling was related to factors other than poliovirus, and those factors could not possibly have been affected by any vaccine.[5]

The belief that polio in general and paralytic polio in particular were rare is not a new belief. In 1961 — only a few years after the introduction of polio vaccines — the following was written in the Chicago Tribune:

Evaluating the true effectiveness of the Salk vaccine and the new oral vaccines has been difficult for several reasons. Polio is a relatively rare disease in the United States. Because so few persons get it in Its paralyzing form, success of an immunizing agent is hard to determine.[6]

And in the year prior to that (1960), Professor Herbert Ratner, M. D., Director of Public Health, Oak Park, said this at the panel discussion “The Present Status of Polio Vaccines” (more on this important discussion later):

Because of the low incidence of polio, neither the private physician nor the local public health physician is in a position to judge the value of polio vaccine from personal experience alone.[7]

The rarity of polio sufferers becoming paralyzed — and the greater rarity of polio sufferers dying — is mentioned in the CDC’s own website:

Fewer than 1% of all polio infections in children result in flaccid paralysis. … The death-to-case ratio for paralytic polio is generally 2%–5% among children and up to 15%–30% for adults (depending on age). It increases to 25%–75% with bulbar involvement.[8]

A case in an article by four medical doctors and a professor of biostatistics has been made that Franklin D. Roosevelt himself, long believed to have suffered from poliomyeltis, probably instead suffered from Guillain-Barre syndrome.[9]

The same authors note,

In 1921 (the year of FDR’s paralysis) the overall incidence of paralytic poliomyelitis in the northeastern United States was estimated to be 3 per 100,000. The true incidence of paralytic poliomyelitis was likely to have been lower, since few, if any, other causes of flaccid paralysis would have been considered at that time.[10]

Regarding the rarity of paralytic polio and how frequently those with polio display symptoms, a World Health Organization document, published in 1954 (the year prior to the polio vaccine campaign), notes:

It must be strongly emphasized that paralysis is an infrequent complication of poliomyelitis infection in man, and that most persons who become infected either show no symptoms or else develop a transient abortive or “minor” illness.[11]

This paints a different picture entirely than Thomas Sowell’s perception — and the perception of society at large — that polio wrought a “reign of terror.”

It must also be noted that an accurate diagnosis of non-paralytic polio was difficult. As the same World Health Organization document reads:

It is not possible to make an accurate diagnosis of non-paralytic poliomyelitis without resort to virological tests, which unfortunately are time-consuming, expensive, and available in only a few centers. …

It must be realized, however, that many other agents cause an aseptic meningitis that cannot be differentiated from non-paralytic poliomyelitis, except by elaborate laboratory tests.[12]

Hence, statistical accuracy would be difficult. This may have also been the case with paralytic polio. The World Health Organization document does state that Guillain-Barre syndrome “may be confused with an extensive paralysis due to poliomyelitis.”[13]

Again, this document was in 1954 — a year prior to the first polio vaccine campaign. Moreover, prior to 1951, distinguishing paralytic polio from non-paralytic polio via national estimates was difficult; paralytic polio was thought to be much more prevalent than it actually was. As the May 1967 issue of Public Health Reports writes,

Separate reporting of paralytic cases began in 1951. Before 1951, the estimate of the incidence of paralytic cases was based on an arbitrary assumption that half the reported cases were paralytic.[14]

Such an arbitrary estimation of paralytic polio surely must have contributed to the needless polio fear of the time.

Additionally, in 1954 (again, the year before the first polio vaccine campaign), the Journal of the American Medical Association points out the difficulty in accurately diagnosing polio:

Despite tremendous strides that are being made in regard to the pathogenesis and epidemiology of acute poliomyelitis, it continues to be one of the most difficult of all diseases to recognize accurately. An increasing amount of experience with this entity has made us approach the diagnosis of this disease with more humility and more respect for the pitfalls that often arise. Knowledge that is accumulating regarding the causative virus, its immunologic response in the human being, and the similarity of the clinical manifestations of this disease to that of other diseases constantly remind us of the many errors that we have undoubtedly made in the past. It is unfortunate that we do not have and will not have in the near future a practical, reliable, inexpensive laboratory test available to all physicians. For this reason we must rely almost entirely on our history and physical examination. The usual laboratory studies, often misleading, are important principally in eliminating the consideration of other diseases.[15]

Thus, not even paralytic polio could easily diagnosed correctly. As noted in the same article, differential diagnoses could be difficult:

When paralysis develops in a patient, the differential diagnosis appears to be simplified. This, unfortunately, is not true as the following cases illustrate. Here the importance of a complete history is self-evident, and the ever-present possibility of pseudoparalysis should be kept in mind.[16]

The article goes on to list those with paralysis who were referred to a particular hospital originally diagnosed with paralytic polio. Diagnoses would be changed to Guillain-Barre Syndrome, brain tumor, pyelonephritis, scurvy, and hysteria.[17]

Indeed, testing methodologies could make all the difference in a correct polio diagnosis. Humphries and Bystrianyk make this interesting observation about the 1958 Michigan epidemic:

As a caseinpoint on how much paralytic disease thought to be polio was not at all associated with polioviruses, consider the well documented Michigan epidemic of 1958. This epidemic occurred four years into the Salk vaccine campaign. An in-depth analysis of the diagnosed cases revealed that more than half of them were not poliovirus associated at all (Figure 12.2 and Figure 12.3). There were several other causes of “polio” besides poliovirus.[18]

They go on to cite “Laboratory Data on the Detroit Poliomyelitis Epidemic 1958” from the Journal of the American Medical Association: — note how the testing methodology exposes how easily one could falsely believe that a polio epidemic exists, as well as how easily certain non-polio infections could be considered to be polio infections:

During an epidemic of poliomyelitis in Michigan in 1958, virological and serologic studies were carried out with specimens from 1,060 patients. Fecal specimens from 869 patients yielded no virus in 401 cases, poliovirus in 292, ECHO (enteric cytopathogenic human orphan) virus in 100, Coxsackie virus in 73, and unidentified virus in 3 cases. Serums from 191 patients from whom no fecal specimens were obtainable showed no antibody changes in 123 cases but did show changes diagnostic for poliovirus in 48, ECHO viruses in 14, and Coxsackie virus in 6. In a large number of paralytic as well as nonparalytic patients poliovirus was not the cause. Frequency studies showed that there were no obvious clinical differences among infections with Coxsackie, ECHO, and poliomyelitis viruses. Coxsackie and ECHO viruses were responsible for more cases of “nonparalytic poliomyelitis” and “aseptic meningitis” than was poliovirus itself.[19]

Finally, in the February 1957 issue of The Atlantic, Dr. David D. Rutstein points out the difficulty in proving the effectiveness of the polio vaccine from 1955-1956 due to wide fluctuations in reported polio cases prior to the vaccine:

The marked drop in reported polio cases from 1955 to 1956 might provide final proof of the value of the vaccine if the number of polio cases in each of the previous years had been relatively constant. As seen in the first diagram, this is not the case. There have been wide swings in the number of polio cases from year to year. Beginning in the 1930s, when reports of polio became fairly reliable, there were a number of years—particularly in the late thirties when there were many fewer cases than in 1956. Following this period, there was a rise in the early 1940s, particularly in 1944 when 19,029 cases were reported. In 1947, for no apparent reason, there was a sharp drop to about 10,000 cases. After that, there were a number of “high polio years” reaching a peak in 1952 with 57,879 cases, which was followed by a drop-off to about half that number in 1955. These fluctuations in the number of cases per year have no known explanation and occur not only in the United States but in many parts of the world. It is of interest that a sharp drop also occurred in England and Wales in these same two years, 1955 and 1956, even though in those countries only 200,000 children had received but one or two injections in a program which began in the late spring of 1956. It is, therefore, impossible to tell whether the decrease from 1955 to 1956 in the United States is a result of the polio vaccine program or whether it is just another sharp swing in the usual pattern of the disease.[20]

The piece goes on to show the difficulty in both knowing how widespread polio was prior to the vaccine, and the difficulty during that time in diagnosing nonparalytic polio; as well as correctly assessing those with paralytic polio:

The total number of cases of polio reported each year includes both paralytic and nonparalytic forms of the disease. When polio occurs without paralysis, it may be difficult to diagnose, particularly in the absence of an epidemic. Nonparalytic polio has to be differentiated from infections due to other viruses, a distinction which medical advances have made possible only during the past few years. When such other virus infections are recognized in epidemic form, as occurred in Iowa in 1956, these cases are properly not included in the total annual figure for polio. Improvement in diagnosis has tended to decrease the number of reported cases of nonparalytic polio in recent years. This in turn makes comparisons of total cases in recent years with previous years less reliable. … Reliable records on numbers of paralytic cases for the United States are available for only the last two or three years, and they are, therefore, not precisely helpful at this time in interpreting the sharp decrease of this year. [21]

And so we see from the outset that polio does not warrant the fears that the vaccine oligarchy would instill in us. Polio is rare in its more benign forms, and much more rare in its paralytic forms. Moreover, as we have seen, it is hard to prove efficacy of the polio vaccine via comparison with the pre-polio vaccination era.

Therefore, justifications for the polio vaccine paradigm have already been practically shattered. But, there is much more to discredit it. If the danger and frequency of the polio disease is over-hyped, so is the efficacy and safety of the vaccine itself (to put it mildly) — as we later show.

Notes

_____________________________________________________

[1] Neil Z. Miller, Vaccine Safety Manual For Concerned Families and Health Practitioners (Santa Fe, NM: New Atlantean Press, 2010, 2015), 47.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ralph R. Scobey, “The Poison Cause of Poliomyelitis And Obstructions To Its Investigation” (Statement prepared for the Select Committee to Investigate the Use of Chemicals in Food Products, United States House of Representatives, Washington, D.C.) (From Archive Of Pediatrics, April, 1952). Retrieved March 1, 2017, from http://www.whale.to/a/scobey2.html.

[4] Suzanne Humphries and Roman Bystrianyk, “The ‘Disappearance’ of Polio,” Dissolving Illusions: Disease, Vaccines, and the Forgotten History (Suzanne Humphries and Roman Bystrianyk, 2013), (online pdf version), 28. Available at https://vaccineimpact.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2016/11/DissolvingIllusions-Polio.pdf.

[5] Suzanne Humphries and Roman Bystrianyk, Dissolving Illusions: Disease, Vaccines, and the Forgotten History (Suzanne Humphries and Roman Bystrianyk, 2013), 224, 225.

[6] Joan Beck, “The Truth About the Polio Vaccines,” Chicago Tribune, volume CXX, no. 10 (March 5, 1961): 8. Retrieved September 7, 2016, from http://archives.chicagotribune.com/1961/03/05/page/62/article/the-truth-about-the-polio-vaccines.

[7] Herbert Ratner, moderator, “The Present Status of Polio Vaccines” (Presented before the Section on Preventative Medicine and Public Health at the 120th annual meeting of the Illinois State Medical Society in Chicago, IL: May 26, 1960) (panel discussion edited from a transcript), Illinois Medical Journal (August 1960): 86. Available online at http://www.greatmothersquestioningvaccines.com/uploads/2/8/8/8/2888885/ratner_1960.pdf.

[8] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases: The Pink Book Home, Poliomyelitis. Retrieved January 18, 2017, from https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/polio.html.

[9] Armond S Goldman, Elisabeth J Schmalstieg, Daniel H Freeman, Jr, Daniel A Goldman and Frank C Schmalstieg, Jr., “What was the cause of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s paralytic illness?” Journal of Medical Biography, 11 (2003): 232-240.

[10] Ibid., 235.

[11] World Health Organization, “Expert Committee on Poliomyelitis: First Report,” World Health Organization Technical Report Series, no. 81. (Geneva, World Health Organization, April, 1954): 7. Retrieved January 16, 2017, from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/40241/1/WHO_TRS_81.pdf.

[12] Ibid., 8, 9.

[13] Ibid. 10.

[14] Leo Morris, John J. Witte, Pierce Gardner, George Miller, and Donald A. Henderson, “Surveillance of Poliomyelitis in the United States, 1962-65,” Public Health Reports, vol. 82, no. 5 (May 1967): 417. Retrieved January 9, 2017, from http://europepmc.org/backend/ptpmcrender.fcgi?accid=PMC1919968&blobtype=pdf.

[15] Robert Britt, Amos Christie and Randolph Batson, “Pitfalls in the Diagnosis of Poliomyelitis,” Journal of the American Medical Association, vol. 154, no. 17 (Chicago, IL: American Medical Association, April 24, 1954): 1401.

[16] Ibid., 1402.

[17] Ibid., 1402-1403.

[18] Humphries and Bystrianyk, “The ‘Disappearance’ of Polio,” Dissolving Illusions: Disease, Vaccines, and the Forgotten History (online pdf version), 15.

[19] G. C. Brown, “Laboratory Data on the Detroit Poliomyelitis Epidemic 1958,” Journal of the American Medical Association, vol. 172, February 20, 1960, 807–812. Cited in Ibid., 15, 16.

[20] David D. Rutstein, “How Good Is the Polio Vaccine?”, The Atlantic (February 1957). Retrieved January 20, 2016 from http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1957/02/how-good-is-the-polio-vaccine/303946.

[21] Ibid.

Roosevelt himself, long believed to have

suffered from it, probably instead

suffered from Guillain Barre syndrome.

Vaccines Contribute to the Spread of Polio

That vaccines have contributed to the spread of polio is well documented, but seldom discussed. Here we included some of that documentation.

For instance, in 1950, a one Dr. McCloskey published a piece in the Lancet titled, “The relation of prophylactic inoculations to the onset of poliomyelitis.”[1] It reads:

Early in the epidemic, attention was directed to a few patients who had been given an injection of pertussis vaccine, or of a mixture of diphtheria toxoid and pertussis vaccine, shortly before the onset of their symptoms.

The parents of these children were naturally inclined to blame the inoculations for the development of the disease, though their medical attendants either dismissed the probability of any causal relationship, or else considered the effect to be due to a radiculitis caused by the vaccine… Considerable evidence, however, will be presented to show that such an association has existed in this epidemic.”[2]

The British Medical Journal (1 July 1950) includes an article discussing those who suffered poliomyelitis paralysis following a 1942 diphtheria vaccination campaign. Similarly, in a subsequent issue (July 29, 1950), the journal includes a piece on those who suffered from poliomyelitis paralysis in 1947 – 1949 who had received pertussis and diphtheria vaccinations.[3]

In 1962, Clinton R. Miller of the National Health Federation, speaking before the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce House of Representatives (87th congress) about polio vaccines, quotes the following from Dr. L. Meyler’s book “Side Effects of Drugs”:

Pertussis vaccine (whooping cough). Up to now some 100 cases of encephalitis have been reported. In half of the cases, the phenomena set in within 6 hours after the injection, and never later than 72 hours. About half of the patients made a complete recovery, about one-third had serious permanent neurological lesions, and about one-sixth died. The increased susceptibility of poliomyelitis is stressed. The value of pertussis immunization is stressed, but so is the grave danger of further Inoculations when a previous one has produced any suggestion of a neurological reaction. … During an epidemic of poliomyelitis, no vaccinations should be given.[4]

(While, unlike Meyler, we wouldn’t endorse pertussis vaccination in any case, Meyler’s comments about its dangers are helpful.)

In an article, Viera Scheibner, author of Vaccination: 100 Years of Orthodox Research shows that Vaccines Represent a Medical Assault on the Immune System, writes:

Let me quote some original seminal medical research.

Anderson et al. (1951) in his article “Poliomyelitis occurring after antigen injections” (Pediatrics; 7(6): 741-759) wrote “During the last year several investigators have reported the occurrence poliomyelitis within a few weeks after injection of some antigen. Martin in England noted 25 cases in which paralysis of as single limb occurred within 28 days of injection of antigen into that limb, and two cases following penicillin injections. In Australia, McCloskey, during a study of the 1949 outbreak, recorded 38 cases that developed within 30 days of an antigen injection, finding an association between the site of paralysis and that of the recently antecedent injection. His findings, contrary to Martin’s suggested a greater association with pertussis vaccine than with other antigens. Geffen, studying the 1949 poliomyelitis cases in London, observed 30 patients who had received an antigen within four weeks, noting also that the paralysis involved especially the extremity into which the injection had been given. In a subsequent survey of 33 administrative areas in England, Hill and Knowelden found 42 children who had been immunized within a month [of injections] … Banks and Beale observed 14 cases that followed within two months after immunization noting also a correlation between site of injection and location of paralysis, as well as increased severity of residual paralysis … In the discussion of this problem during the April 1950 meeting of the Royal Society of medicine, Burnett and others stressed the apparent relationship to multiple antigens containing a pertussis component”. [undoubtedly reflecting the increasing use of pertussis-containing vaccines].[5]

Moreover, according to Eleanor McBean, a one William F. Koch (M.D., Ph.D.), has stated,

The injection of any serum, vaccine, or even penicillin, has shown a very marked increase in the incidence of polio, at least 400%. Statistics on this are so conclusive, no one can deny it.[6]

So, ironically, while the polio vaccine’s alleged victory over polio (a myth that we debunk in this article) is used to manipulate parents into vaccinating their children , it appears that vaccinating children has contributed to polio. And so if we are really concerned about ending polio, ending vaccines is a good place to start.

But, there’s more; later in this piece, we show that not only has non-polio vaccination contributed to the spread of polio, but polio vaccination itself has.

Notes

_____________________________________________________

[1] Viera Scheibner, Vaccination: 100 Years of Orthodox Research shows that Vaccines Represent a Medical Assault on the Immune System (Santa Fe, NM: New Atlantean Press, 1993), 143.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid., 143, 144.

[4] Cited in Clinton R. Miller, “Statement of Clinton R. Miller, Assistant to the President, National Health Federation, Washington, D.C.” (Intensive Immunization Programs, May 15th and 16th, 1962. Hearings before the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce House of Representatives, 87th congress, second session on H.R. 10541), 85. Retrieved February 15, 2017, from http://www.whale.to/v/greenberg1.pdf.

[5] Viera Scheibner, “Re: Polio eradication: a complex end game,” The Bmj (April 10, 2012). Retrieved September 9, 2016, from http://www.bmj.com/content/344/bmj.e2398/rr/578260. [6] Cited in Eleanor McBean, The Poisoned Needle: Suppressed Facts About Vaccination (Pomeroy, WA: Health Research, 2005), 104.

virtually ignored by vaccine propagandists

when it comes to disease eradication.

Is Vaccination the Only Explanation for the Decline of Polio?

Polio supposedly decline due to the use of the polio vaccine. Later in this piece we more thoroughly refute this idea, but for the time being let’s consider some other factors.

We previously have shown that what we know about the extent of polio prior to the vaccination campaign is less than reliable. For what it’s worth, there are some who have made the case, based on perhaps the best information that they had, that polio and polio death rates were already on the decline prior to the vaccine. (Thus, to the extent that we rely on data prior to the polio vaccine, this information must be considered.)

Not only this, but it has been argued that polio declined in Europe prior to the extensive use of vaccines.

We don’t often hear that polio was in decline prior to the polio vaccine program; and yet, according to consultant neurosurgeon Dr. Miguel A. Faria, Jr.,

In the 1950s, there were 20,000 cases of polio annually causing more than 1,000 deaths; many more thousand victims were left in iron lungs. This was caused because of the predilection of the polio virus for the anterior horn cells of the spinal cord and consequent paralysis of the respiratory muscles. But, what is less known, and this is quite disconcerting to me, is that between 1923-1953, before the Salk (dead virus) vaccine was discovered in 1955, the polio death rate in the U.S. and England declined on its own by 47 percent and 55 percent, respectively. This is not reported or discussed by the public health establishment but, it seems, only by independent researchers … neither is the fact that European countries, which didn’t systematically immunize their citizens, also experienced a precipitous decline in their polio morbidity and mortality statistics.[1]

Faria credits “better hygiene and sanitation and better living conditions” for “bringing down the number of cases of polio.”[2] (Dr. Thurman Rice once said, “It is not strange that health improves when the population gives up using diluted sewage as the principle beverage” [1932]). Indeed, the CDC itself states this about improved sanitation’s effect on polio:

In the immediate prevaccine era, improved sanitation allowed less frequent exposure and increased the age of primary infection.[3]

Professor Herbert Ratner, M. D., Director of Public Health, Oak Park, referring in 1960 to a graph titled “The Natural Rise and Fall of Two Diseases Poliomyelitis (1942-1959) [and] Infectious Hepatitis (1949-1959),” writes, “Both diseases were in a natural decline when the Salk vaccine was introduced in 1955.”[4] (See graph on page 2 here.) Should we, then, credit the Salk vaccine for the decline in infectious hepatitis?!

Pointing to International Mortality Statistics in 1981, medical research journalist Neil Z. Miller writes:

From 1923 to 1953, before the Salk killed-virus vaccine was introduced, the polio death rate in the United States and England had already declined on its own by 47 percent and 55 percent, respectively. Statistics show a similar decline in other European countries as well.

[5]

Miller adds:

[W]hen the vaccine did become available, many European countries questioned its effectiveness and refused to systematically inoculate their citizens. Yet, polio epidemics also ended in these countries.[6]

Further information for consideration regarding the decline in polio in the U.S. and other countries is seen in a 1957 article in The Atlantic by Dr. David D. Rutstein. (The American polio vaccine campaign had already began in 1955.) He writes:

The marked drop in reported polio cases from 1955 to 1956 might provide final proof of the value of the vaccine if the number of polio cases in each of the previous years had been relatively constant. As seen in the first diagram, this is not the case. There have been wide swings in the number of polio cases from year to year. … These fluctuations in the number of cases per year have no known explanation and occur not only in the United States but in many parts of the world. It is of interest that a sharp drop also occurred in England and Wales in these same two years, 1955 and 1956, even though in those countries only 200,000 children had received but one or two injections in a program which began in the late spring of 1956. It is, therefore, impossible to tell whether the decrease from 1955 to 1956 in the United States is a result of the polio vaccine program or whether it is just another sharp swing in the usual pattern of the disease.[7]

And so, regarding the end of polio epidemics in Europe, Dr. Robert S. Mendelsohn, who served as chairman of the Medical Licensing Committee for the State of Illinois and associate professor of Preventative Medicine and Community Health in the School of Medicine of the University of Illinois, asks this important question:

It is commonly believed that the Salk vaccine was responsible for halting the polio epidemics that plagued American children in the 1940s and 1950s. If so, why did the epidemics also end in Europe, where polio vaccine was not so extensively used?[8]

Could it be, then, that the pro-vaccine paradigm is simply stealing from the benefits of improved hygiene and sanitation?

Ironically, vaccine propagandists — against all sense of proportionality — dismiss the countless accounts of children who have been killed (e.g, “sudden infant death syndrome”) or injured (e.g., “autism”) by vaccines by saying, “correlation doesn’t necessarily mean causation,” and yet — quite hastily and simplistically — ignore their own advice when disease supposedly declines following widespread use of vaccines.

It is not just improved hygiene and sanitation that can result in the decline of disease; diseases can decline for other reasons — and may even disappear suddenly with no explanation.

As reported in the Report of the Medical Officer of Health by the City of Glasgow (1958),

The causes of decline of an epidemic are difficult to define. Weather conditions are an obvious factor. It is also reasonable to think that the building up of herd immunity in the population plays a part. This increasing immunity has in past epidemics been due to natural infection. In 1958 natural and artificial immunisation worked in parallel. It is suggested, with some diffidence, that the critical level of herd immunity was reached more quickly as a result of vaccination.[9]

In referring to “artificial immunisation,” the report holds that the polio vaccine played a role in reducing polio, an idea that we shall challenge more later. However, it does acknowledge that diseases can decline for other reasons (e.g., weather conditions). It even notes that “herd immunity” can be achieved via natural infection, and acknowledges its role in reducing polio after the polio vaccine was introduced.

The London Medical and Surgical Journal (1832) makes this observation about epidemics:

As yet the cholera has not caused a great mortality, and if we reflect upon the mysterious course of epidemic diseases in all ages and countries, it appears to us, notwithstanding the great predisposition or liability of the Irish to the cholera, it may, like thousands of other epidemics, suddenly disappear; or effect much less mortality than on slight consideration might be expected. In our last Number there was ample proof of this statement afforded in the article on the epidemic diseases of Ireland, by which it appeared, that the devastating pestilence of 1348, which was so fatal in every part of Europe, and especially in England, was comparatively limited in its effects on the inhabitants of Ireland. In the present instance, time alone must determine the correctness or incorrectness of our assertion.[10]

While discussing cholera, the following is said in the British Medical Journal (1865):

Probably, as measles, scarlet fever, small-pox, etc., mysteriously flash out, and still more mysteriously disappear, so would it have been here. To induce those mighty epidemics that desolate a world, there must be something more—some great pervading influence, that science only knows from its effects.[11]

In an 1877 report from the U.S. Department of the Interior, we read:

Thus, even a calamity, under certain circumstances, can be rendered advantageous to a certain point, as, for instance, it is a well established fact that after heavy storms malignant epidemics suddenly disappear.[12]

More recent statements are found in Ebola Virus Disease: From Origin to Outbreak by Dr. Adnan I. Qureshi:

The third pattern is the “tooth eruption” pattern where, like the tooth hidden within the gums and emerging indepedent of other teeth, the pathogen emerges and is exterminated without any relation to previous occurences. The Ebola virus is one of the pathogens following the “tooth eruption” pattern where the disease emerged in Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) in 1976, disappeared, and then reemerged in Uganda between September 2000 and February 2001, only to mysteriously disapear. It emerged again in December 2013 in Guinea.

What is far more perplexing is why epidemics die their deaths, a phenomenon noticed since the beginning of humanity. While it is convenient to believe that measures such as vaccination of at-risk individuals, quarantine of diseased persons, and acute and timely treatment are the cause of epidemic eradication, the facts do not support such a conclusion. In fact, the largest epidemics, such as the Peloponnesian War Pestilence, Antonine Plague, Plague of Justinian, Black Death of the fourteenth century, and Spanish flu, came to an end without widespread use of any of those strategies.[13]

Regarding polio itself: after the national polio vaccine program was implemented, Oak Part, IL, Health Commissioner Herbert Ratner, M.D., in 1956 writes in the Journal of the American Medical Association that poliomyelitis was not only uncommon, but that many factors unrelated to vaccination have been keeping it at bay:

The Idaho data simply confirms the fact that poliomyelitis is a low-incidence disease and that there is a high degree of acquired immunity and many natural factors preventing the occurrence of the disease (as contrasted to an “infection”) in the Nation at large. … Everyone should recognize that 1955 was a low poliomyelitis year independently of the use of the Salk vaccine, which was only given to 9 million children.[14]

Having said all those, let us now turn to one of the quickest way to make a disease “decline” — statistical manipulation.

Notes

_____________________________________________________

[1] Miguel A. Faria, Vaccines (Part II): Hygiene, Sanitation, Immunization, and Pestilential Diseases (Journal of American Surgeons and Physicians, ) (Originally published in the March/April 2000 issue of the Medical Sentinel. Association of American Physicians and Surgeons, 2000). Retrieved April 15, 2015, from http://www.jpands.org/hacienda/article36.html.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases: The Pink Book Home, Poliomyelitis. Retrieved January 31, 2017, from https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/polio.html.

[4] Herbert Ratner, moderator, “The Present Status of Polio Vaccines” (Presented before the Section on Preventative Medicine and Public Health at the 120th annual meeting of the Illinois State Medical Society in Chicago, IL: May 26, 1960) (panel discussion edited from a transcript), Illinois Medical Journal (August 1960): 85. Available online at http://www.greatmothersquestioningvaccines.com/uploads/2/8/8/8/2888885/ratner_1960.pdf.

[5] Neil Z. Miller, “The Polio Vaccine, Part 2: The polio vaccine: a critical assessment of its arcane history, efficacy, and long-term health-related consequences,” VaxTruth (March 20, 2012). Retrieved January 23, 2016, from http://vaxtruth.org/2012/03/the-polio-vaccine-part-2-2. Miller draws from Alderson M., International Mortality Statistics, Washington, DC: Facts on File, 1981:177–8.

[6] Ibid.

[7] David D. Rutstein, “How Good Is the Polio Vaccine?”, The Atlantic (February 1957). Retrieved January 20, 2016 from http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1957/02/how-good-is-the-polio-vaccine/303946.

[8] Robert S. Mendelsohn, How to Raise a Healthy Child … In Spite of Your Doctor (NY: Ballantine Books, 1987), 231.

[9] City of Glasgow, Report of the Medical Officer of Health (The Corporation of the City of Glasgow, 1958), 131. Retrieved March 15, 2017, from https://archive.org/stream/b28652459#page/130/mode/2up.

[10] Michael Ryan, ed., “Cholera in London, Dublin, and Paris” (May 5, 1832, vol. 1, no. 14), The London Medical and Surgical Journal; Exhibiting a View of the Improvements and Discoveries in the Various Brances of Medical Science, vol. I (London: Renshaw and Rush, 1832), 441.

[11] D.B. White, Northern Branch: President’s Address, Transactions of Branches (December 2, 1865), in William O. Markham, ed., The British Medical Journal, Being the Journal of the British Medical Association, vol. II for 1865, July to December (London: Thomas John Honeyman), 576.

[12] Department of the Interior, United States Geological Survey, F.V. Hayden, U.S. Geologist-in-Charge, First Annual Report of the United States Entomological Commission for the Year 1877 Relating to the Rocky Mountain Locust and the Best Methods of Preventing its Injuries and of Guarding Against its Invasions, in Pursuance of an Appropriation Made by Congress for this Purpose, with Maps and Illustrations (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1878), Appendix III: Texas Data for 1877, 72.

[13] Adnan I. Qureshi, Ebola Virus Disease: From Origin to Outbreak (San Diego, CA: Elsevier, 2016), 40.

[14] Herbert Ratner, “Poliomyelitis Vaccine,” Journal of the American Medical Association (Jan. 21, 1956). Cited in Intensive Immunization Programs, May 15th and 16th, 1962. Hearings before the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce House of Representatives, 87th congress, second session on H.R. 10541, 89. Retrieved February 15, 2017, from http://www.whale.to/v/greenberg1.pdf.

“prove” any point

Don’t Blindly Follow Statistics (even those in support of Vaccines)

While many aren’t willing to admit it when it doesn’t suit their purpose, statistics can be easily manipulated — and are regularly done so to further one agenda or another. Entire books have been written on this subject. As one author notes,

There are several undeniable truths about statistics: First and foremost, they can be manipulated, massaged and misstated. …

Second, if bogus statistical information is repeated often enough, it eventually is considered to be true.[1]

And so,

It is a fact that facts are stubborn things, while statistics are generally more pliable … figures don’t lie, but liars figure. You can torture numbers and they will confess to anything. And statistics mean never having to say you are sorry.[2]

Indeed, it is quite easy to “produce” statistics behind closed doors, and then pass them on to the public as “facts”; all that it requires is trust on the public’s part. But beyond this, statistics can be incorrect even when produced sincerely. As economist Thomas Sowell writes,

In the real world … even without ideological bias or manipulation, statistics can be grossly misleading.[3]

This doesn’t mean that we have to be cynical about all statistics; but we shouldn’t blindly embrace whatever statistics are put before us — especially when they defy biblical truths and common sense, or when there is evidence of manipulation. Indeed, man is fallen and finite, and so he too often sets out to deceive — and even when he doesn’t, he too often misses the full picture.

And so, we ought not to think that vaccine statistics are immune to manipulation (especially since they are a highly profitable business). In fact, Dr. Archie Kalokerinos — who witnessed firsthand illness and death inflicted by vaccines on the Aborigine people — said:

[T]he further I looked into it the more shocked I became. I found that the whole vaccine business was indeed a gigantic hoax. Most doctors are convinced that they are useful, but if you look at the proper statistics and study the instance of these diseases you will realise that this is not so.[4]

Some testify to such statistical manipulation when it came to smallpox vaccines (which, we are told, eradicated smallpox). According to Dr. Russell of the Glasgow Hospital, “Patients entered as unvaccinated showed excellent marks (vaccination scars) when detained for convalescence.”[5] This could obviously influence statistics. Moreover, Lilly Loat, in The Truth About Vaccination and Immunization, writes:

In his Report for the year 1904 Dr. Chalmers, Glasgow M.O.H., stated that inquiries had been made of Registrars of Births in connection with smallpox cases entered as “unvaccinated” or “doubtful”; and 10 of the “unvaccinated” and 20 of the doubtful “were found to have been certified as having been successfully vaccinated in infancy.“[6]

Jno. Pickering, F.S.S., F.R.G.S., writes in the 1876 book The Statistics of the Medical Officers to the Leeds Small-Pox Hospital Exposed and Refuted,

I know very well that the statistics as to the cases and deaths of the vaccinated and unvaccinated are published for a purpose — a purpose that is unworthy and contemptible — it is simply to deceive the public mind, and to withdraw all consideration from the rationale of vaccination, … The Statistics of the Vaccinator are not to be trusted … The Vaccinator has a craze to support, and he will do it even at the sacrifice of truth.[7]

Pickering goes on to say:

My suspicions, as to the untrustworthiness of Medical Statistics, were first roused in March, 1872, but my enquiries were confined to the small-pox deaths. It never once occurred to me that, either from carelessness or audacity, the Medical Officers would include among the “unvaccinated,” living examples of the “successfully vaccinated.” During that month I investigated the particulars as to 16 deaths which had taken place in the Hospital between the 29th January and the 9th March, 1872. Of these 16 deaths the Medical Officers had returned 9 unvaccinated, 6 vaccinated, and 1 unknown. After a full and careful enquiry, which occupied Mr. Kenworthy and myself for several days, I attended before the Board of Guardians and handed in a return showing that the 16 deaths were composed of 12 vaccinated patients, 2 unvaccinated, and 2 unknown. The two unvaccinated were two out of the three cases “certified unfit,” being scrofulous from birth, and the two unknown were Irish vagrants, who had neither friend nor relative in the country who could give any account of them. Out of the 16 deaths there was, not one fair unvaccinated case. After all the trouble I took in this matter, neither the Board of Guardians nor the Medical Officers accepted my challenge to have a public enquiry.[8]

Dr. Charles Creighton (1847-1927) was a scholar, historian, and epidemiologist who initially supported vaccines. But after being asked to write an article on the topic for the Encyclopedia Britannica, he exhaustively studied the subject and found vaccination to be in error. On smallpox statistical manipulation, he writes in the said article:

The returns from special smallpox hospitals make out a very small death-rate (6 per cent.) among the vaccinated and a very large death-rate (40 to 60 per cent.) among the unvaccinated. The result is doubtful qua vaccination, for the reason that in pre-vaccination times the death-rate (18.8 per cent.) was almost the same as it is now in the vaccinated and unvaccinated together (18.5). At the Homerton Hospital from 1871 to 1878 there were admitted 793 cases in which “vaccination is stated to have been performed, but without any evidence of its performance”; the deaths in that important contingent were 216, or 27.2 per cent., but they are not permitted to swell the mortality among the “vaccinated.” Again, the explanatory remarks of the medical officer for Birkenhead in 1877 reveal to us the rather surprising fact that his column of “unvaccinated” contained, not only cases that were admittedly not vaccinated, but also those that were “without the faintest mark”; of the 72 cases in that column no fewer than 53 died. His column of “unknown” contained 80 per cent, of patients who protested that they had been vaccinated (28 deaths in 220 cases or 127 per cent.). Those who passed muster as veritably vaccinated were 233, of whom 12 died (51 per cent.). With reference to this question of the marks, it has to be said that cowpox scars may be temporary, that their “goodness “or “badness ” depends chiefly on the texture of the individual’s skin and the thickness or thinness of the original crust, and that the aspect of the scar, or even its total absence some years or even months after, may be altogether misleading as to the size and correctness in other respects of the vaccine vesicle, and of the degree of constitutional disturbance that attended it. This was candidly recognized by Ceely, and will not be seriously disputed by anyone who knows something of cowpox and of how it has been mitigated, and of the various ways in which the tissues of individuals may react to an inoculated infection. In confluent cases the marks on the arm would be less easily seen.[9]

Was smallpox ever conveniently redefined to make it appear that the smallpox vaccine was effective? According to George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950), yes.

During the last epidemic at the turn of the century, I was a member of the Health Committee of London Borough Council. I learned how the credit of vaccination is kept up statistically by diagnosing all the re-vaccinated cases (of smallpox) as pustular eczema, varioloid or what not — except smallpox.[10]

M. Beddow Bayly, M.R.C.S., L.R.C.P., in The Case Against Vaccination (1936), writes:

Between 1881 and 1924, in England and Wales, out of a total of 20,810 deaths only 5,508 were classified as unvaccinated, and these figures become more striking still when we realise that in deciding the diagnosis of the many “doubtful” cases it has been asserted by one Medical Officer after another that vaccination within ten years practically rules out the possibility of a case being smallpox, and the Ministry of Health itself has admitted that the vaccinal condition is a guiding factor in diagnosis….

Besides the admission of doctors themselves, one of the proofs of the dishonest “cooking” of official records is the attributing of an increasing number of deaths to chicken-pox; in the thirty years ending 1934, 3,112 people are stated to have died of chicken-pox, and only 579 of smallpox, in England and Wales. Yet all authorities are agreed that chicken-pox is a non-fatal disease; Sir William Osier (who himself contracted smallpox, although vaccinated several times) gave it as his opinion that such cases were probably “unrecognised smallpox,” and, he might have added, “in the vaccinated.” It was admitted before the Royal Commission that official doctors did not classify cases as vaccinated unless they could distinguish the marks, and that in severe cases the latter were frequently obscured by the eruption. Yet in spite of these and other sources of error which must be taken into account when examining any tables dividing cases into vaccinated and unvaccinated cases, in England and Wales at the present time the fatality among the vaccinated is over twice as great as among the unvaccinated, i.e., .51 per cent, compared with .21 per cent, for the years 1922-1933.[11]

Of more recent history, there are questions as to whether the CDC tried to suppress the findings of CDC Epidemiologist Dr. Thomas Verstraeten linking vaccines and autism, as well as findings linking Merck’s MMR vaccine to an explosion in autism among African American boys (under 3).[12] (The latter is discussed in the sobering documentary Vaxxed, which is waking up the world to the dangers of vaccines.)

Perhaps more on statistics regarding non-polio vaccines later in the series (as the polio vaccine is the main focus of this piece). From what we have discussed, however, we should be thinking more critically when it comes to statistics — and know that not even vaccine statistics are immune from being erroneous or fraudulent. In fact, we now turn to statistical manipulation as applied to the polio vaccine itself.

Notes

_____________________________________________________

[1] Robert Rector, “Statistics can be manipulated to prove anything,” Pasadena Star-News/News (May 24, 2014). Retrieved April 7, 2016, from http://www.pasadenastarnews.com/general-news/20140524/statistics-can-be-manipulated-to-prove-anything.

[2] Rick Kirschner, Insider’s Guide to the Art of Persuasion: Use your Influence to Change Your World (Ashland, OR: Rick Kirschner, 2007), 134.

[3] Thomas Sowell, The Vision of the Anointed: Self-Congratulation as a Basis for Social Policy (Basic Books, New York, NY: 1995), 53.

[4] Archie Kalokerinos, “Interview,” International Vaccine Newsletter (June 1995). Retrieved September 16, 2016, from http://www.whale.to/v/kalokerinos.html.

[5] G. Miller, ed., To Doctor Alexander J. G. Marcet, London, 11 November 1801, Letters of Edward Jenner and Other Documents Concerning the Early History of Vaccination (London, England: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1983), xxxv. Cited in Neil Z. Miller, Vaccine Safety Manual For Concerned Families and Health Practitioners (Santa Fe, NM: New Atlantean Press, 2010, 2015), 32.

[6] Lilly Loat, The Truth About Vaccination and Immunization (1951). Retrieved April 22, 2016, from http://www.whale.to/a/stat2.html.

[7] Cited in Ibid.

[8] Cited in Ibid.

[9] Charles Creighton, “Vaccination,” in Encyclopaedia Britannica, 9th Edition (1888). Cited in 1902encyclopedia.com. Retrieved April 25, 2016, from http://www.1902encyclopedia.com/V/VAC/vaccination.html.

[10] G. Miller, ed., To Doctor Alexander J. G. Marcet, London, 11 November 1801, 64. Cited in Miller, Vaccine Safety Manual For Concerned Families and Health Practitioners, 32.

[11] M. Beddow Bayly, The Case Against Vaccination (1936). Retrieved May 2, 2016, from http://www.whale.to/vaccines/bayly.html.

[12] Speed The Shift, “The Conclusive Evidence Linking Vaccines and Autism,” VisionLaunch (February 8, 2016). Retrieved April 3, 2017, from http://visionlaunch.com/the-conclusive-evidence-linking-vaccines-and-autism/.

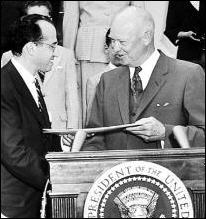

Salk a medal for his polio vaccine.

In reality, the disease was not

conquered by the vaccine, but by

a stroke of the pen,

redefining the disease.

“Polio” Conveniently Redefined Following the Release of the Vaccine

It is widely assumed that the polio vaccine vanquished polio. Statistics, after all, support this. However, as we have already discussed, statistics can be easily manipulated. Could this have been the case about statistics favoring the polio vaccine? Did the polio vaccine make polio disappear— or did a stroke of the pen make the polio vaccine’s inability to vanquish polio disappear?

According to a piece in The Vaccine Reaction,

Perhaps the most egregious example of clever sleight of hand (… not to mention the outright, blatant rewriting of history) on the part of public health officials in the United States occurred in 1954 when the U.S. government changed the diagnostic criteria for polio. It was the year that medical researcher and virologist Jonas Salk produced his inactivated injectable polio vaccine (IPV). The vaccine was licensed in 1955 and began to be used to inoculate millions of children against polio.

The Salk vaccine has been widely hailed as the vanquisher of polio, and it is commonly used as the shining example of how vaccines are the miracle drugs for combating infectious diseases… and now even against diseases that are not infectious. Pick any disease, illness or disorder you want. You got cancer, cholera, peanut allergies, stress, obesity… we’ll develop a vaccine for it. …

What is conveniently omitted from this heroic story is that the reason the number of polio cases in the U.S. dropped so precipitously following the mass introduction of the Salk vaccine in 1955 was not medical, but rather administrative. …

[I]n 1954 the U.S. government simply redefined polio.[1]

Back in 1961, an article in the Chicago Tribune discusses this redefinition of polio:

The definition of polio also has changed in the last six or seven years. Several diseases which were often diagnosed as polio are now classified as aseptic meningitis or Illnesses caused by one of the Coxsackie or Echo viruses. The number of polio cases in 1961 cannot accurately be compared with those in, say 1952, because the criteria for diagnosis have changed.[2]

The article draws attention to a panel discussion that took place before the Illinois State Medical Society in Chicago in May 1960. Titled “The Present Status of Polio Vaccines,” the discussion includes a panel of experts who debunk myths about polio vaccines that society had already come to embrace.

(The experts for this discussion, which we draw on throughout this piece, include panel moderator, Herbert Ratner, M. D., Director of Public Health, Oak Park, and Associate Clinical Professor of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, Stritch School of Medicine, Chicago; Dr. Herald R. Cox, “one of the world’s leading authorities” on live and killed vaccines; Dr. Herman Kleinman, an epidemioloist “intimately connected” with the Minnesota Department of Health’s “pioneering field studies on the Cox live poliovirus vaccine,”; Professor Meier, a biostatistician known for an analysis titled “Safety Testeing of Poliomyelitis Vaccine,”; and Professor Bernard G. Greenberg, “head of the department of statistics of the University of North Carolina, School of Public Health and former chairman of the Committee on Evaluation and Standards of the American Public Health Association,” who has “presented several papers on methodologic problems in the determination of the efficacy of the Salk vaccine.”)[3]

In the discussion, the statistician and professor Bernard G. Greenberg comments on the redefinition of “paralytic poliomyelitis”:

This change in definition meant that in 1955 we started reporting a new disease, namely, paralytic poliomyelitis with a longer lasting paralysis. Furthermore, diagnostic procedures have continued to be refined. Coxsackie virus infections and aseptic meningitis have been distinguished from paralytic poliomyelitis. Prior to 1954 large numbers of these cases undoubtedly were mislabled as paralytic poliomyelitis. Thus, simply by changes in diagnostic criteria, the number of paralytic cases was predetermined to decrease in 1955-1957, whether or not any vaccine was used.[4]

(Note that he says that not only was paralytic poliomyelitis redefined, but “diagnostic procedures have continued to be refined.” Indeed, paralytic polio was redefined outright, while non-paralytic polio would be redefined via a more stringent testing criteria.)

This statistical manipulation was not insignificant. As panel moderator Dr. Herbert Ratner notes, the changes were radical (in his words: “radical changes in diagnostic criteria since the introduction of the Salk vaccine.”).[5]

Greenberg describes the radical differences in diagnosing paralytic polio before and after 1954:

The criterion of diagnosis at that time [prior to 1954] in most health departments followed the World Health Organization definition: “Spinal paralytic poliomyelitis: Signs and symptoms of nonparalytic poliomyelitis with the addition of partial or complete paralysis of one or more muscle groups, detected on two examinations at least 24 hours apart.”

Note that “two examinations at least 24 hours apart” was all that was required. Laboratory confirmation and presence of residual paralysis was not required. In 1955 the criteria were changed to conform more closely to the definition used in the 1954 field trials: residual paralysis was determined 10 to 20 days after onset of illness and again 50 to 70 days after onset. The influence of the field trials is still evident in most health departments; unless there is a residual involvement at least 60 days after onset, a case of poliomyelitis is not considered paralytic.[6]

Thus in their book discussing the history of vaccines, Dr. Suzanne Humphries and Roman Bystrianyk write:

The practice among doctors before 1954 was to diagnose all patients who experienced even short-term paralysis (24 hours) with “polio.” In 1955, the year the Salk vaccine was released, the diagnostic criteria became much more stringent. If there was no residual paralysis 60 days after onset, the disease was not considered to be paralytic polio. This change made a huge difference in the documented prevalence of paralytic polio because most people who experience paralysis recover prior to 60 days.[7]

The epidemiologist Dr. Kleinman, at the same panel discussion as Dr. Greenberg, called the 60 day criterion “absolutely silly”:

I would also like to agree with Dr. Greenberg that the insistence upon a sixty day duration of paralysis for paralytic polio is absolutely silly. There isn’t a doctor in this room who hasn’t seen a case of frank paralytic polio which has not recovered within sixty days, or at least recovered sufficiently so that you could not estimate with clinical certainty that there was some residual paralysis.[8]

Moreover, in 1962, Clinton R. Miller of the National Health Federation, speaking before the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce House of Representatives (87th congress) about polio vaccines, called the redefinition of paralytic polio “like comparing a sneeze and pneumonia.”[9]

Now, it would be hard to make the case that Greeberg, Kleinman, and others were conspiring to falsely make us believe in a new 60 day criterion for diagnosing paralytic polio. Regarding diagnoses of paralytic polio prior to 1955, Greenberg, as was mentioned, quotes the World Health Organization.

And he didn’t make that quote up. The World Health Organization document, published in 1954, is here (see p. 23 to confirm Greenberg’s quote). Quoting directly from the document, we read:

A patient is considered clinically to have poliomyelitis for purposes of notification if the symptoms and signs correspond with the following descriptions: …

Spinal paralytic poliomyelitis:Signs and symptoms of non-paralytic poliomyelitis with the addition of partial or complete paralysis of one or more muscle groups, detected on two examinations at least 24 hours apart.[10]

The Ratner Report points to another source showing that there was no 60-day requirement for diagnosing paralytic polio prior to 1955 [11] from The National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (founded by Franklin D. Roosevelt; what we now know as the March of Dimes). In a 1954 pamphlet titled “Definitive and Differential Diagnosis of Poliomyelitis,” the National Foundation makes this similar statement about paralytic poliomyelitis to that of the World Health Organization:

Paralytic Poliomyelitis

Definition: The signs and symptoms of nonparalytic poliomyelitis with evident weakness of one or more groups of muscles.[12]

Nothing in the pamphlet — including the section on classification — refers to a requirement of 60 days for a diagnosis of paralytic polio.

Regarding the diagnosis of paralytic polio post-1955, we find that that very year, a national poliomyelitis surveillance program was created. As noted in a 1967 Public Health Reports piece by those in the National Communicable Disease Center of the Public Health Service,

A NATIONAL Poliomyelitis Surveillance Program was created by the Suregon [Surgeon] General of the Public Health Service in April 1955. Since that time, this program has served not only as a clearinghouse for the collection, analysis, and distribution of epidemiologic information on poliomyelitis in the United States, but also as a means of continuous surveillance of the disease and evaluation of the safety and efficacy of poliomyelitis vaccines. Since May 1, 1955, Poliomyelitis Surveillance Reports have been published regularly and distributed to those charged with responsibility for control of the disease.[13]

And so, the same piece affirms the 60-day requirement (as well as diagnoses without followup) for diagnosing paralytic polio:

Cases of paralytic poliomyelitis with residual paralysis have been considered the best continuing index of paralytic disease, and they form the basis of the subsequent presentation in this paper. These cases include (a) those with residual paralysis at 60 days and (b) preliminary diagnosis of paralytic poliomyelitis with no 60-day followup.[14]

The 60-day requirement is further confirmed on the CDC’s website.

Confirmed [paralytic poliomyelitis]: Acute onset of a flaccid paralysis of one or more limbs with decreased or absent tendon reflexes in the affected limbs, without other apparent cause, and without sensory or cognitive loss; AND in which the patient

- has a neurologic deficit 60 days after onset of initial symptoms, or

- has died, or

- has unknown follow-up status.[15]

Now, to the “elimination” of polio via vaccination. Regarding a graph by the Ratner Report comparing the incidence of poliomyelitis between 1951-1959, vaccine researcher Shawn Siegel writes: “30,000 cases a year we were subsequently told were eliminated by the vaccine.”[16] Statistical manipulation can yield impressive results.

But, it gets worse. Further cultivating the perception that the polio vaccine was effective, the definition of a polio epidemic was changed:

As addressed in the Ratner report, they also changed the definition of a polio epidemic, greatly reducing the likelihood that any subsequent outbreaks would be so labeled – as though the severity, or noteworthiness, of paralytic polio had halved, overnight.[17]

Ratner states this in the report: “Presently [1960], a community is considered to have an epidemic when it has 35 cases of polio per year per 100,000 population.”[18] In a footnote, the report reads:

Prior to the introduction of the Salk vaccine the National Foundation defined an epidemic as 20 or more cases of polio per year per 100,000 population. On this basis there were many epidemics throughout the United States yearly. The present higher rate has resulted in not a real, but a semantic elimination of epidemics.[19]